On Darwinism: “In the struggle for survival, the fittest win out at the expense of their rivals because they succeed in adapting themselves best to their environment.”

– Civilizations Past & Present, 1960

Often, it is not the strongest that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one most adaptable to change. Darwin’s Origin of Species has suggested that adaptation is a critical part of the evolutionary process and it is rewarded. Capital, in its purest form, understands this and, when left to market forces, will flow to those areas and enterprises that adapt most within the evolutionary process.

Central to our investment process is understanding how the global financial landscape is changing and implementing a strategy that best adapts. While the pandemic has temporarily stunted economies globally, it has also exposed more fundamental vulnerabilities. No more apparent is this than with the world’s second largest economy – China – and the crossroads in which it finds itself today.

As a result of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, China responded by rapidly expanding credit creation in the areas of fixed investment and real estate. For many years, this appeared to be a sufficient strategy – GDP continued to grow, as did global demand for the proliferation of low-value-added manufacturing in China. But by the end of the last decade, credit in China was well north of US$45 trillion. In fact, China’s credit growth rate since 2008 was close to 20% per year. Many would suggest that the apparent growth in output was just the typical credit-fueled growth bubble that so many economies have experienced.

The Debt Death Trap?

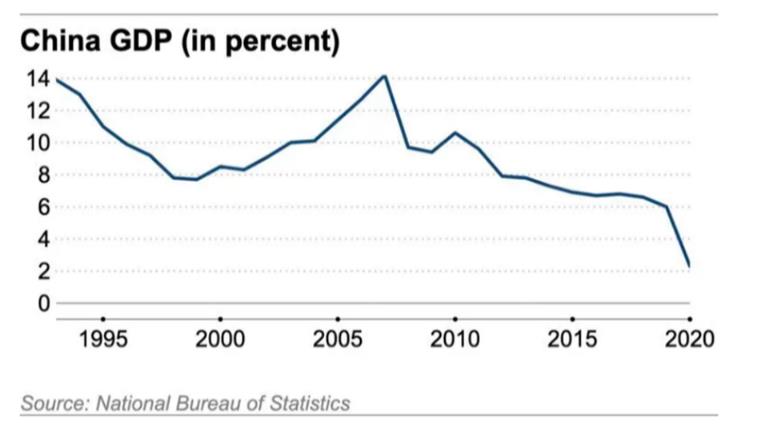

One major problem stemming from the credit-fueled growth in infrastructure and real estate was the significant amount of unproductive assets, or bad debt, which eventually accumulated. As a result, China could experience a massive banking crisis in the future. Beijing has responded by adjusting its policies to significantly slow credit growth and try to pivot the economy towards more high-value-added enterprises and consumption. As a result, China has seen a substantial reduction in GDP growth.

Table: Growth in China Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in %, 1990 to 2020

Adding to the problem has been a declining workforce, a consequence of the 1979 one-child policy, which ended in 2015. Economists point to the “Lewis Turning Point,” named after Arthur Lewis who postulated that once an economy has reached the point at which the workforce can no longer supply cheap labour to the production process, an evolutionary process must begin. Rising wages (and the resultant inflation) will erode the global competitive advantage that China has held in low value-added manufacturing.

Economists refer to the stage in which the Chinese economy now finds itself as the “middle-income trap.” To escape this trap, significant structural adjustments are required. This includes the need for a change in the composition of Chinese GDP, to be based more on services, consumption and higher value-added manufacturing.

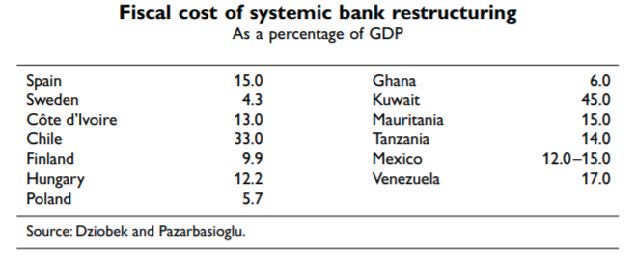

Through history, we have seen many examples of countries that were unsuccessful in overcoming the middle-income trap. After all, an economy that only lives off new funding will eventually crash. Typically, the status quo, which has gained political power and wealth, fights against this pivot, precipitating a banking crisis that stops the country’s evolutionary process in its tracks. The table below shows the fiscal cost of banking crises in select countries – the sheer magnitude is testimony to the repercussions.

Table: The High Cost of Systemic Bank Restructuring

Beijing is well aware of the consequences and was on its way to implementing policies to prevent the collapse of its banking system and pivot its economy. Yet, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, it was forced back to the old playbook to support the economy: targeting credit creation for infrastructure projects and allowing regional governments to issue bonds for new projects, while relaxing credit conditions for real estate purchases. This helped China achieve GDP growth of 2.3% in 2020. To be clear, Beijing had limited tools at its disposal. With the excessive level of credit in the banking system, policymakers could not use a massive credit-driven, investment-led stimulus effort.

However, this was the lowest level of growth in over 44 years since the Cultural Revolution devastated the economy in 1976. Looking more closely, we see that exports (up 18%) significantly outperformed imports (up 1%), pointing to lower consumption (down 4%), weak labour markets and increased manufacturing overcapacity. The 7% increase in real estate development, 3% increase in fixed investment and 15% increase in semiconductor imports suggest that long-term imbalances expanded while advancement in technology lagged.

For Now: A Crouching Dragon

Eventually the tables must turn. China still faces a massive debt crisis, but understands the need to pivot its economy to overcome the middle-income trap – an undertaking which we assume will be successful. Policymakers in Beijing will need to reverse course and, in the process, investors should take heed. The crouching dragon – China’s temporary slowdown – should not come as a surprise. Investors should expect an adjustment period where growth in China decelerates in areas such as fixed investments and real estate, concomitantly reducing demand for commodities. During this period, the growth baton will be passed to sectors supported by strong secular growth themes, such as digitization, alternative intelligence, and machine learning, to name a few.

Our belief is that this occurrence may also amplify the possibility of a growth scare that may be further exacerbated by sluggish vaccine deployment globally. As we get later into the year, we would expect concrete success in opening the global economy to replace these growth fears. At that time, investors may want to consider investments that benefit from an acceleration of global growth, and the acceleration of inflation fears. But, for now, as the world’s second largest economy taps the brakes and reverses policies implemented to generate growth at any cost in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, investors should not be confused. China cannot and will not rely on the credit fuel growth that has carried it through previous decades.

James E. Thorne, Ph.D.