“Sometime before the year 2025, America will pass through a great gate in history, one commensurate with the American Revolution, Civil War and twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War II.”

— The Fourth Turning, William Strauss & Neil Howe

Strauss and Howe’s book, “The Fourth Turning,” describes the recurring generational cycle in American and global history that unleashes a new social, political and economic environment. Today, we are in the midst of extreme generational change, akin to those periods that historians analyze for decades to come. While extreme change often feels unsettling, investors should take notice for the opportunities that may arise.

For most investors, generational shifts are not easily identified until well after they have taken place. Back in 1982, if I told you that we were about to embark on an over three-decade deflationary journey, would you have believed it? Or, in the early 1990s, that we would eventually spend one quarter of our life on the internet?1 At that time, the fax machine was seen by many high-profile commentators2 as a more critical piece of technology to society. In both cases, most investors failed to take a step back and recognize that the context of our world had changed.

Central Bankers: A Generational Pivot

Indeed, the context of our world is once again changing. Over the summer, US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivered one of the most important speeches in recent memory. At the Kansas City Federal Reserve Symposium, he finally admitted publicly what many have known for some time: the policies that central bankers have followed since the 1980s have led to deflation and contributed to the rise of populism. He termed this: “Volcker Disinflation.”3

It was in 1979 when Paul Volcker dramatically changed the course that central bankers would follow for four decades. Inflation – more specifically, wage inflation – was not to be tolerated. But this would lead to the longer-term consequences we see today: the managed decline of Western economies, a falling standard of living for the middle class and a rise in income inequality and populism. Now, Powell – the most powerful man in the policy-making world – was admitting that the old playbook of central bankers needed to be put to bed.4 This ushered in a new movement that suggested that inflation needs to run above its 2% target for an extended period of time. Policy makers also conceded that using interest rates as a policy tool was flawed.5

The Lessons of Economics 101 Don’t Apply: Surprise!

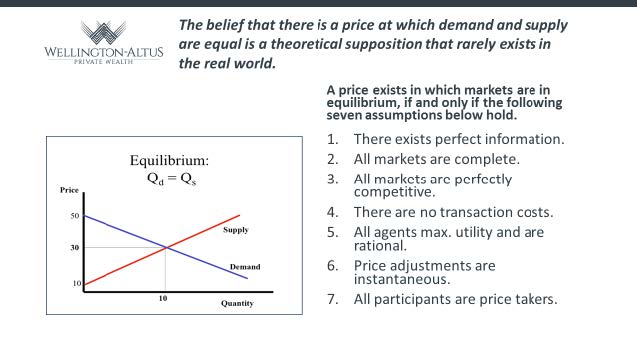

Economics 101 teaches students that there is a special price (in this case, interest rates) that can be found when markets are in equilibrium, such that supply and demand intersect. But this is a theoretical supposition that doesn’t take place in the real world. Equilibrium can only be achieved if certain conditions, as contained in Table 1 (see next page), are met.

In the real world, markets very rarely meet these conditions and it is certainly true that credit markets don’t either. Markets are never in equilibrium; they are what economists refer to as “rationed markets.” Credit is allocated by “a system that makes judgements,”6 violating the conditions required for price, and only price, to clear the market. What determines when a transaction is complete is the side of the market that has the lesser quantity, either demand or supply.

It follows that in rationed markets, policymakers need to focus on the quantity component. The economic theory we were taught was wrong! Market equilibrium can be achieved by policymakers focusing on the quantity of credit in the real economy – and not its price.

Table 1: Economics 101 – Market Equilibrium

History supports this view. Takahashi Korekiyo, known as the Japanese Keynes, famously abandoned the gold standard in late 1931, introducing a major stimulus program in coordination with the creation of bank credit that rescued the Japanese economy from the Great Depression well before the US. During the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt focused on housing in the 1930s as the main element of the American Dream. Through the innovation of the guaranteed 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, credit was funneled into the real economy. Again, in the 1980s, Japan, through its “window guidance” policy, forced banks to supply credit to Main Street. What followed was a decade of strong economic growth and innovation. In 2014, the Bank of England explicitly stated that credit is created by “commercial banks making loans.”7 To be clear, commercial banks do not simply act as financial intermediaries, but are a critical element in creating credit for the real economy. But since 2009, regulations have been put in place to make it less profitable for commercial banks to create credit.

Where to From Here?

If policymakers are aware that interest rate policy is flawed and they must instead focus on credit creation to generate real economic growth, the big question is why haven’t they? Until more recently, the problem has been that to do so would undermine the Central Bank’s position of political neutrality. However, this all changed in March 2020, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The question of why it has taken so long for a regime change is not our focus. Our intention is to suggest that when we see a generational shift in central bank policy, whether explicit or implicit, investors need to take notice. As Winston Churchill said: “never let a good crisis go to waste.”

The key for investors is to look for implicit forms of credit creation in the real economy. If we can find them, then our bullish view of economic recovery, risk assets and the coming inflationary environment is reinforced. We also emphasize the importance of Mr. Powell’s assertion that the “notable lack of the emergence of some sort of financial bubble” in spite of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion suggests that a financial asset bubble does not currently exist. History has shown that financial bubbles pop when the supply of credit is stopped. This happened in the late 1990s when supply of credit to the internet companies abruptly ended.

Today, credit creation is just starting to be directed into the real economy. Investors should not expect explicit declarations in policy changes, but should instead be on the lookout for subtle indications in regulation, policy stance and cooperation between fiscal and monetary authorities.

Behind the scenes, this has been happening. When Madame Lagarde took over as the Head of the European Central Bank, she stated her desire to “explore every avenue in order to combat climate change.” She is not alone: the central banks of 63 nations, including Canada, have created an organization focused on “greening” the financial system. The Network for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS) was established at the Paris One Planet Summit in December 2017 to strengthen the global response to climate change and mobilize capital for green investments. This sounds surreptitiously like targeted credit creation.

Table 2: Behind the Scenes – The NGFS

In 2020, corporate bond issues have doubled from levels seen in 2019. Tesla, for example, raised $2 billion in late February and has signaled the desire to raise another $5 billion according to recent SEC filings. This is hardly a sign that credit is being cut off. Verizon, a big player in the corporate bond market, just raised $1 billion in green bonds, of which proceeds must be directed toward projects that reduce their carbon footprint, not share buybacks or dividends. JP Morgan also recently raised $1 billion issuing green bonds. In the second quarter, close to $100 billion of sustainable bonds were issued globally. The green bond market is forecast to reach $1 trillion by the end of 2021. The German government, following Sweden, Poland and France, just announced its desire to issue green bonds.

On the regulation side, the US FCC accelerated a clearing program designed to free up mid-band spectrum for 5G. The mid-band spectrum is important as it supports broad geographic coverage and speedy connections. This puts the US one step closer to releasing significant portions of spectrum needed to help compete against the Chinese. Under the surface, the deregulation strategy implemented by the Trump administration has created an environment which drives demand for credit. Perhaps a sign of things to come, in Wyoming, cryptocurrency exchange Kraken has become the first crypto company to receive a bank charter. Too few recognize these regulatory changes as a driving force for the demand for credit that can generate future real economic growth. We are still early in this economic cycle.

Central bankers are now open to targeted credit creation. With the help of fiscal policy, this may be the bridge the global economy needs when the Covid-19 pandemic recedes. Investors with a longer time frame should be open to the opportunities this may present. What should investors do?

- Recognize that the Central Bank playbook developed in the 1980s is no longer in use.

- Be on the lookout for programs that target credit growth to Main Street. It’s about the supply of credit, not the price of credit.

- Central banks are willing to let the economy run hot; interest rates will be low for the foreseeable future.

- The greening of the world economy may be the policy used to generate strong economic growth. Other programs such as 5G may also catch the eye of central banks.

- The cycle will end when the supply of credit stops!

Investors should take notice. Western economies are once again passing through the gates of history.

James E. Thorne, Ph.D.

1 www.digitalinformationworld.com/2019/02/internet-users-spend-more-than-a-quarter-of-their-lives-online.html

2 Bill Gates and Paul Krugman, to name just a few.

3 New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review, J. Powell. “Navigating the Decade Ahead: Implications for Monetary Policy Symposium”, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, WY, August 2020.

4 He suggested that there was no causal relationship between wage growth and general price inflation: The Phillip’s Curve is dead!

5 This wasn’t the first time that central bankers suggested conventional practices may not be working. Then-Governor of the Bank of England, Marc Carney stated in his March 2016 speech that if monetary policy (i.e. interest policy) cannot generate the economic growth needed, help is required.

6 Stiglitz 2002. Globalization and its Discontents.

7 Money Creation in the Modern Economy, The Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1.