“Just because you despise me, you are the only one I trust.”

(Casablanca, 1942)

Perhaps one of the greatest films of all time, Casablanca is a love story about an American expat facing the moral dilemma of choosing between his love for a woman and helping the escape of her husband, a French Resistance leader. The film is set in the French protectorate of Morocco in December 1941, the same month that the bombing of Pearl Harbor pushed the Americans into war. When it was released in 1942, it was viewed as a political allegory about the extreme structural changes unleased by World War II. While the war would continue for almost three more years, the reconstruction period would prove pessimists wrong and lead the U.S. into a post-war boom.

We suggest that the Covid-19 pandemic, along with the rise in populism, has created an environment that mirrors this period. We are entering a reconstruction phase. Today, a pivot by global central bankers – changes in policy responses, efforts to reduce income inequality and a focus on green initiatives – has created a foundation that is ripe for a commodities supercycle. After a decade of underinvestment, the despised energy and commodities sectors will be big winners and investors should take notice.

History: Post WWII Reconstruction

The period of the early 1940s to 1951 provides a good parallel for the post-pandemic world that is emerging today. During WWII, fiscal stimulus coupled with monetary policy continued to boost domestic economic activity and prop up the economy. Most economists believed that as soon as the war ended, these stimulus measures would also end and the economy would fall into recession, largely because of the experiences after WWI and the previous decade of the Great Depression.

Yet, it was those fears, combined with the decision to continue to hold down Treasury financing costs, which led the government to continue its bond-support program for much longer than needed to simply achieve a price stability goal. The reconstruction period focused on retraining the workforce, reducing income inequality and generating sufficient demand. The Federal Reserve and the Treasury worked in tandem to ensure strong economic growth was achieved while keeping interest rates from rising to the point where financing the excess government debt hindered economic growth.

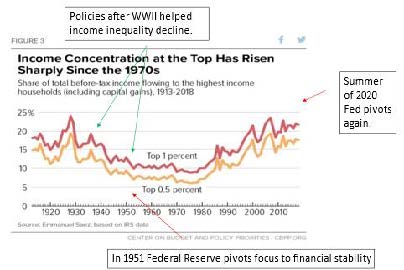

Despite the war ending in 1945, these efforts largely continued until 1951. This era ended when China entered the Korean War and the USSR started to move into Berlin. Americans, fearing war, responded by hoarding goods which led to explosive inflation and forced the Federal Reserve to adopt a new focus on financial and price stability, setting the stage for the long march towards the rising income inequality we see today.

Chart: Income Inequality Rises as the Fed Focuses Primarily on Financial Stability

Today: Post-Pandemic Reconstruction – The Fed Pivot

The World Economic Forum has used the analogy of a post-war reconstruction period when suggesting how post-pandemic recovery should be viewed: “To achieve a better outcome,” said Klaus Schwab, Executive Chairman, “the world must act jointly and swiftly to revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions.

Every country, from the United States to China, must participate, and every industry, from oil and gas to tech, must be transformed. In short, we need a ‘great reset’ of capitalism.”

The Covid-19 pandemic is the global event that will force elected politicians and policymakers of the official sector to no longer ignore the dual issues of income inequality and climate change. While the Federal Reserve has often been positioned as an apolitical institution divorced from global social needs, throughout history it has pivoted when economies have been confronted with social discourse: the rise of fascism and income inequality of the 1920s, the fear of a post-WWII economic collapse and the war on poverty in the 1970s.

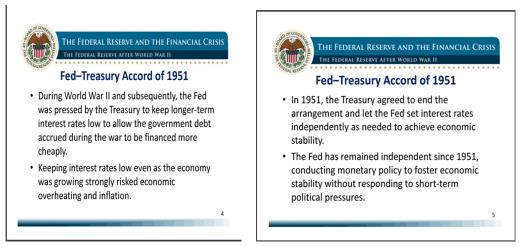

In 2010, then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, reintroduced actions taken by the Fed during 1942 to 1951, emphasizing the critical role the Fed played in helping to rebuild the western economy: increased wages and jobs, supporting the Marshall Plan – an American initiative passed in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe, largely to help prevent the spread of social discourse – and keeping inflation well behaved.

Chart: Ben Bernanke 2010 Federal Reserve Presentation

After WWII, the Fed was more concerned about growth and income inequality. Financial stability concerns only came into focus in 1951.

For decades, global central bankers and investors were concerned about escaping the liquidity trap caused by the extreme level of debt to GDP, and the accompanying low level of economic growth and deflationary pressures that led to negative interest rates. Bernanke’s solution was to create an environment where investors felt the Fed was behind the curve, while at the same time maintaining credibility, and strong growth for real economic goods counteracting the deflationary forces of technology.

Today it seems as though Chairman Powell is following a similar playbook and may again be perceived to be behind the curve.1 We may be surprised at how slowly the Fed raises interest rates, comfortable with the rise in inflation because it sees it as being transitory. This lack of concern is likely to cause many investors to fret. We are about to experience a rapid increase in economic activity, in which the U.S. economy could reach full employment faster than ever. The post-pandemic economic growth burst, along with short-term interest rates being kept low, will bring a steepening yield curve. Inflation may be allowed to run to levels where cries of hyperinflation will be heard. Yet, we suggest that these fears will be misplaced. Alas, this is how every secular inflation period begins – this time is no different! To be clear, rising inflationary expectations, along with well-behaved real inflation, will motivate consumers and decision-makers to expedite consumption or investment decisions. This is precisely the silver bullet that policymakers need to achieve.

An Emerging Commodity Supercycle?

The two basic ingredients required for a commodity supercycle are an extended period in which capital investment has been lacking and a secular demand shock. Today we have both.

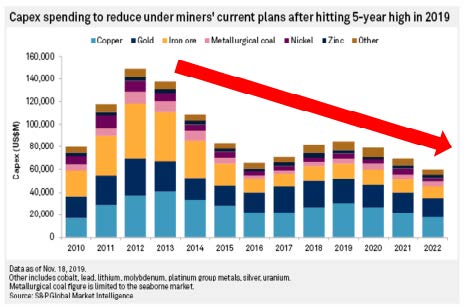

Over the past decade, the commodities sector has largely been despised by investors. Among Wall Street and company management teams, there has been a lack of investment across the sector, driven more recently by greater attention to the green economy. The pandemic has amplified this situation, resulting in lower demand due to the economic shutdowns. As such, companies have been pressured into returning capital to investors, instead of reinvesting it in their operations.

Chart: Decline in Capital Expenditures in the Mining Sector

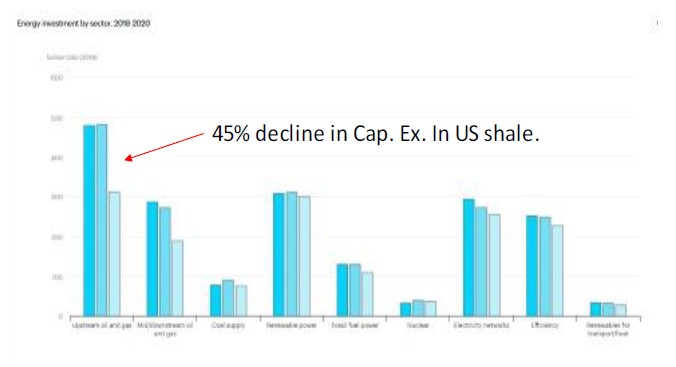

Just how pronounced has the decline in investment been? The oil industry has been particularly hard hit. IEA research shows a dramatic drop of 45% in capital expenditures in 2020 for the U.S. shale plays, a subsector that has experienced a surge of bankruptcies, layoffs and shut-ins, as well as a 50% increase in financing costs.

Chart: Decline in Capital Expenditures of U.S. Shale Plays

As is always the case, significant under-investment in capital expenditures is one of the foundational requirements for a supercycle. This creates tighter supply, which then sets the stage for a period of price increases. But what will happen as a result of the demand shock that occurs with the re-opening of the global economy? This will force new supply back onto the market and entice increased capital expenditure investments to create new supply. The key difference in this cycle: the looming move towards the green economy. As such, investment will be focused on projects that return capital quickly to investors. In the last supercycle, Canada was a clear winner. Yet, in the oft-despised oil sector, the U.S. shale plays are set to be greater beneficiaries with their shorter lead-time for capital investment to come to fruition.

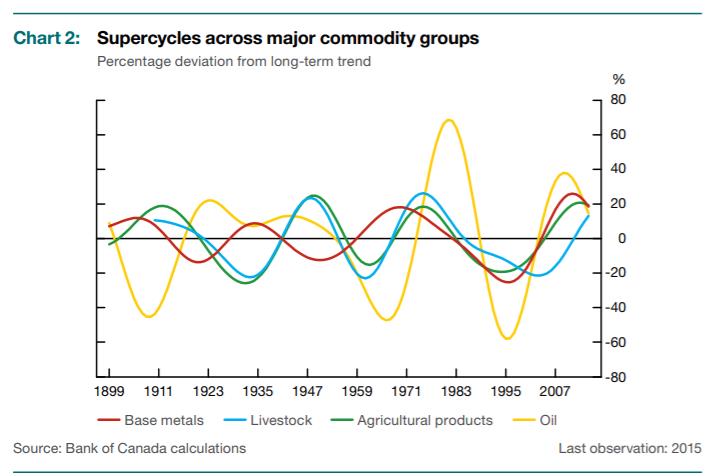

Chart: Bank of Canada Data: Commodity Supercycles in Canada

All of this is taking place in an ESG investing environment which has suggested that, after 2030, the consumption of commodities will rapidly decline based on climate goals set by nations globally. Despite the threat that the green economy poses to certain commodities subsectors, it will also create demand. Building the new green infrastructure will be a commodity-intensive driver. Massive infrastructure will be needed globally to transition off of fossil fuels. To put into context the size of the potential demand, in the decade before the global financial crisis China spent close to $10 trillion building infrastructure to facilitate the rapid urbanization of its economy.

The timing for decreased commodities demand should also be viewed with some skepticism. The period beyond 2030 will likely see divergences – as decarbonization accelerates, demand for commodities linked to high-carbon activities should decline rapidly. Companies will not waste capital on building a mine or a long-duration energy asset that takes 10 years to build, and will be pressured to return capital to shareholders. Yet, with no fewer than 189 countries committing to zero carbon, the shape and speed of decarbonization efforts will be different for each country and sector. Demand for commodities may extend further than many believe; we saw this with the sustained demand shock from the rapid urbanization of China that began in the early 2000s.

The evolution of the relationship of the west with China may also change demand dynamics. Bringing supply chains back home for critical commodities is now a matter of national security. In the 1970s, the Cold War with Russia motivated countries to have ample domestic inventories of agricultural products. If we see a similar return to protecting national interests, it could usher in a strong decade for soft commodities.

More profoundly, we are seeing the roll out of one of the most significant .S. stimulus programs. Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, recognized for boldly ignoring traditional Wall Street pundits, is focused on economic stabilization and reducing income inequality. It appears that Biden is slowly wading into the waters of modern monetary theory (MMT) – debt does not matter, as long as growth can be generated – likely leading to further massive spending, including his proposed $2 trillion green infrastructure bill: stay tuned.

Indeed, the foundation for a commodities supercycle has been firmly planted. As the post-Covid-19 world unfolds and policymakers focus on social discourse, and with a green plan to build back better, the strong cyclical recovery will usher in a new era of secular inflation that has the potential to embrace a new commodities supercycle.

Investors who allocate capital early are likely to realize, in the words of Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca:

“I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

James E. Thorne, Ph.D.