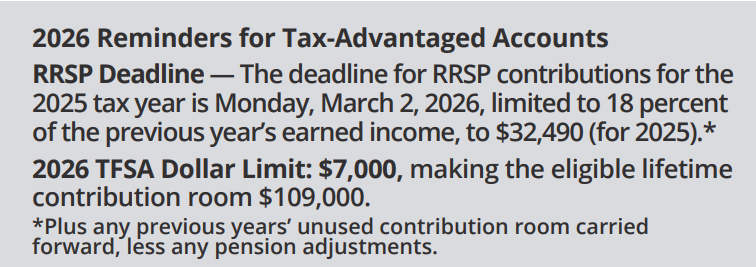

While many of us are unhappy about the high taxes we pay, one way to ease the burden is by fully using tax-advantaged accounts. Yet RRSP participation rates have declined over the past two decades, from 29.1 percent of taxpayers in 2000 to just 21.7 percent in 2022. The good news: high-income earners are more likely to contribute: 66 percent of taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $500,000 contributed in 2023. But younger Canadians are falling short. The introduction of the Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) in 2009 may be part of the reason, but persistent misconceptions about the RRSP also play a role. Let’s address two common myths:

Myth 1: It’s better to invest in a TFSA than an RRSP. In fact, the RRSP generally yields a greater benefit if you expect a lower tax rate in retirement. In practice, many contribute to their RRSP during higher-income working years and withdraw when income is lower in retirement, leading to an advantage for the RRSP. Of course, there may be situations when the TFSA is a better choice, such as if you have a higher tax rate at withdrawal or face recovery tax for income-tested benefits like Old Age Security.

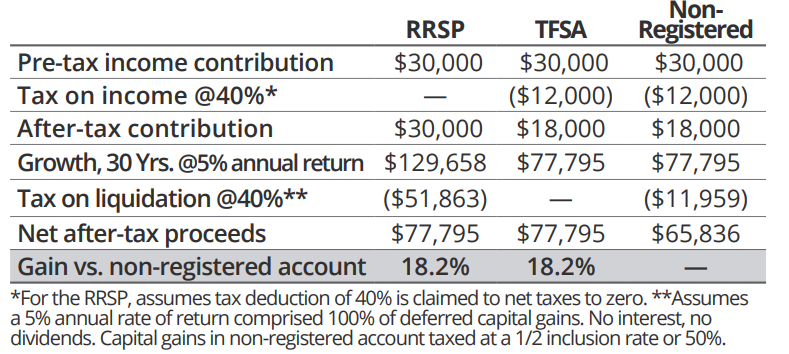

Myth 2: RRSPs aren’t worth it because withdrawals are fully taxed, whereas in non-registered accounts, only income and gains are taxed. A common complaint is that RRSP withdrawals are fully taxed at marginal rates, whereas non-registered accounts only tax income and gains (with favourable tax treatment for dividends and capital gains). While it’s true that RRSP withdrawals (usually from a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF)) are taxed as income, what’s often forgotten is the initial tax deduction at contribution. Remember: a $30,000 RRSP contribution is equivalent to an after-tax contribution of $18,000 at a marginal tax rate of 40 percent. If your tax rate is the same at the time of contribution and withdrawal, you effectively receive a tax-free rate of return on your net after-tax RRSP contribution (chart). In many cases, even if your tax rate is higher at the time of withdrawal, you may be better off compared to a non-registered account due to the effect of tax-free compounding over long time periods.

While the fair market value of the RRSP/RRIF at death is generally included in the terminal tax return and taxed at marginal rates, there may be ways to mitigate the potential tax liability. This includes a tax-deferred rollover to a spouse or financially dependent (grand)child. Another way to manage the potential tax bill is to engage in a “meltdown strategy,” making withdrawals earlier when your tax rate is lower than you expect in the future or at the year of death.