Both China and the USA, and for that matter, Trump and Xi, are striving for greatness just as Michael Jordan did in the 1990s. In “The Last Dance” documentary, which introduced a generation to possibly the greatest basketball player of all time, Michael Jordan used slights and signs of disrespect, real or imagined, to propel himself and teammates to historic levels of success, catapulting the NBA into a global brand. In a broader context, we see similar techniques used in the current tensions between China and the US, and specifically by President Trump and Chairman Xi. While much of the rhetoric is noise directed towards a domestic audience, investors should recognize that the situation is fragile and could unravel quickly. In the middle of this is Hong Kong, for many the fulcrum point that could ignite the next global financial crisis. While constructive on the current capital market outlook, an escalation in the Hong

Kong crisis, specifically a breaking of the Hong Kong dollar peg to the US dollar, is a risk that investors should contemplate.

History reveals that the need for capital is a common theme in the rise and fall of global powers. When the United States emerged victorious from its revolutionary war with the British empire, and started to implement the policies put forth in Alexander Hamilton’s “Report on Manufacturing”, London was forced to pivot and focus on trade with China to try and generate the capital required to sustain its vast empire. What ensued was the opium wars and for the Chinese, the beginning of 100 years of humiliation. During this period China was forced to lease the island of Hong Kong to the United Kingdom.

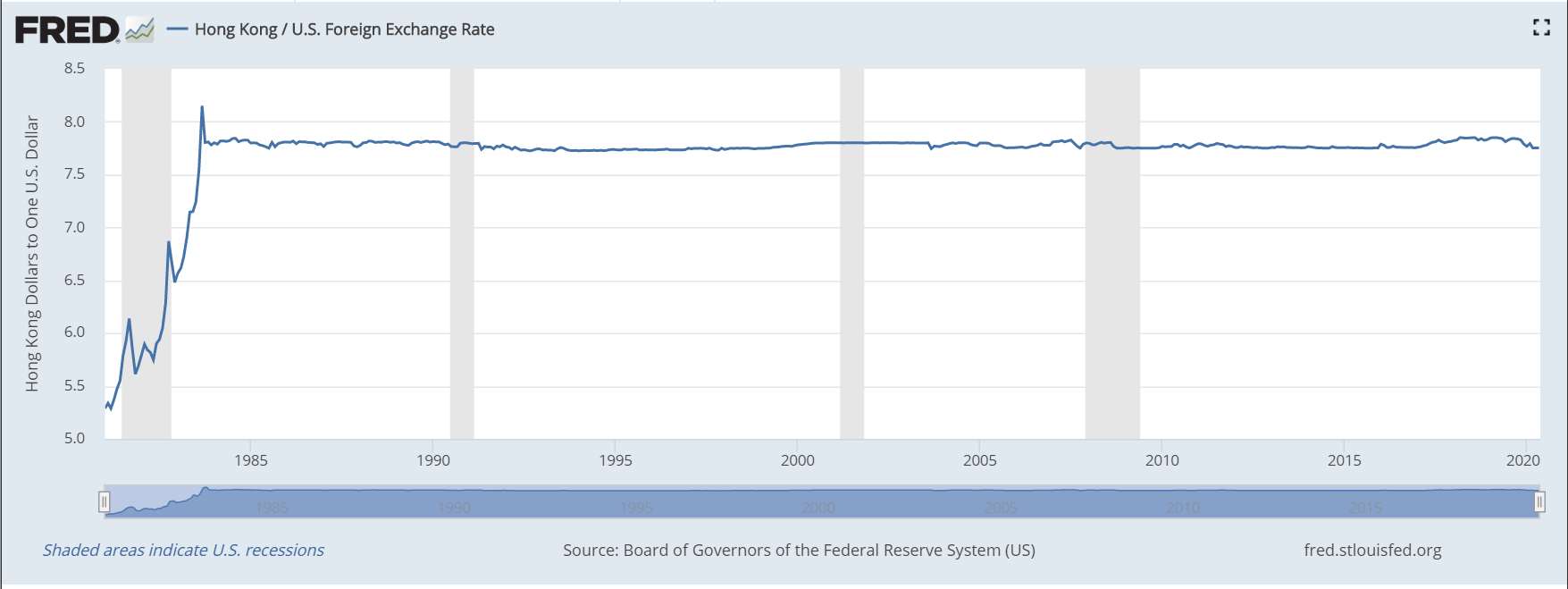

Fast forward to the late 1970s and China first introduces market forces into the economy after Chairman Mao’s death, ironically following loosely the plans set forth by Alexander Hamilton. There was however one notable exception, China did not want to open its financial markets, instead choosing to finance its evolution internally. In the early stages of opening, Hong Kong became the port of entry for most goods going into China, becoming the largest port in the world. In the early 1980s with the end of the 100-year lease fast approaching, and with news that the UK was in negotiations to hand control of the island back to China, the Hong Kong dollar exchange rate was pegged (fixed) to the US dollar in order to calm financial markets. True to form, with the hand over approaching in 1997, the Hong Kong peg was attacked by mass selling from speculative traders. To fend off the attack, the Hong Kong monetary authority had to significantly raise interest rates. This sacrificed its real estate market, resulting in a banking crisis in mainland China where banks had significant exposure to Hong Kong real estate. It took years for the banks to be restructured, with nonperforming loans reaching 20% by some estimates.

By fixing its currency to the US dollar, Hong Kong accepts the interest rate policy of the Federal Reserve, which in 2009 was set to zero. China’s policy response was to support its lofty GDP growth targets through massive domestic credit creation. Hong Kong for a period got the best of both worlds, unfortunately, all good things must come to an end. Total domestic credit in China stands north of $45 trillion, a 20% growth rate since 2008. The prevailing view has been that eventually China will have to abandon its 6% plus growth target, substantially reduce domestic credit growth, and open its financial market to international participants. The results of the Plaza and Louvre accords in the 1980s on the then

globally dominant Japanese economy however does not escape Chinese policymakers.

Furthermore, the recent policy by the Trump administration concerning investing in Chinese Stocks, and the listing of American Deposit Receipts (ADRs) by Chinese companies points to a concerted effort to cut off capital flows. With supply chains in China also being redirected back to the US, another source of foreign capital is being reduced. With the need to achieve the goals laid out in the communist party’s five-year plan coming due in 2021, will China throw caution to the wind and continue to expand internal credit to achieve its goals? Or will they make a deal with Trump?

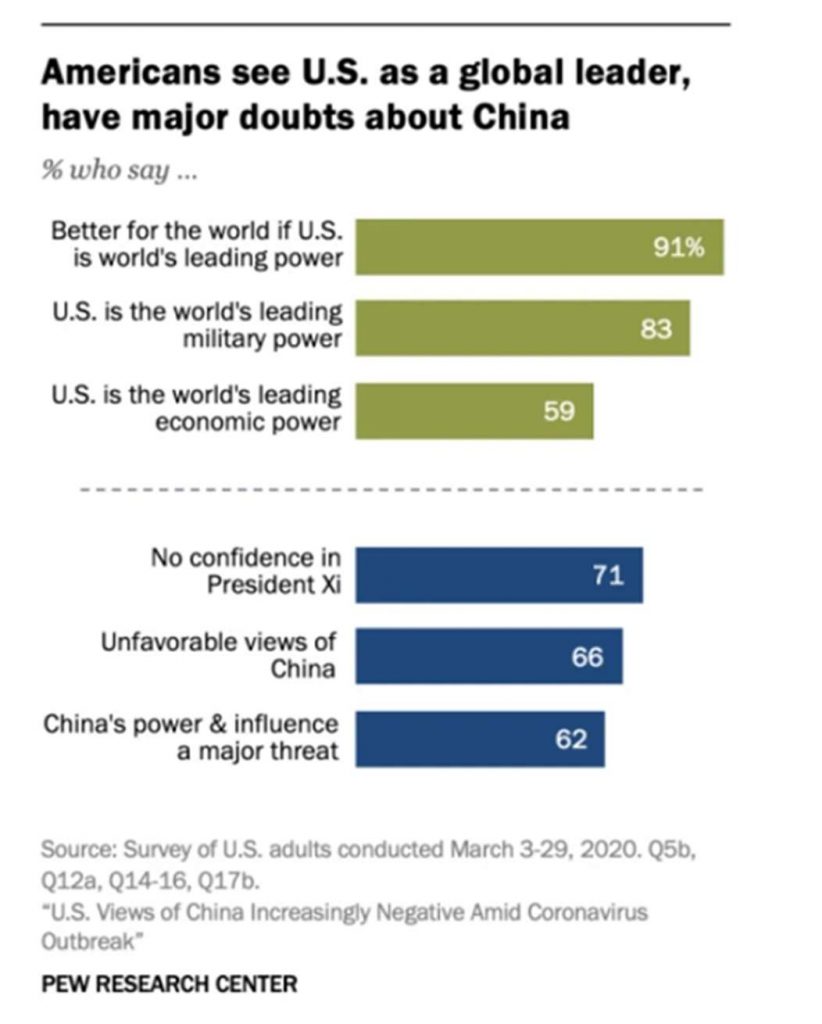

My grandmother would say to me, don’t play with fire or you might get hurt. In this presidential election year, will Trump escalate tensions with China? Is chairman Xi willing to play with fire? President Trump likes to have leverage when negotiating, and many suggest he has it. According to the Pew Research Center, 91% of Americans have a negative view towards China.

With the Covid-19 pandemic stoking an already high level of paranoia in the US, investors should not be surprised if the Hong Kong peg to the US dollar is attacked by speculators. Currently, Hong Kong contains the two key elements required for a financial crisis: excess and complacency. What will be the igniting event? Only time will tell, for now the signal investors need to focus on is the peg, and ignore the noise XI and Trump are generating with their rhetoric.

James E. Thorne Ph.D. May 23, 2020.