Navigating An Era Of Fiscal Dominance, Rate Cuts And Debt Monetization

Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it. – Sir Winston Churchill

The Ghost of Arthur Burns

U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, deeply mindful of Arthur Burns’ missteps and inspired by Paul Volcker’s tenacity, is fully cognisant of the historical significance of his role. I have consistently argued that Powell would benefit from studying William McChesney Martin’s tenure as the first post-Second World War Federal Reserve Chair in the 1950s. Martin adeptly navigated through a period of fiscal dominance, a pattern that is emerging once again. As Sir Winston Churchill implied [1], focusing on the wrong historical period can lead to policy errors and financial turmoil.

British economist John Maynard Keynes, speaking at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, cautioned the U.S. about the perils of a fiat currency [2], particularly with the dollar as the world’s reserve. He predicted the temptation for governments to rely on money printing instead of tax increases or spending cuts, which could spur inflation or deflation and jeopardize economic stability. Keynes pointed to a recurring theme where nations fall into fiscal recklessness, devalue their currency, and decline, as seen with the Roman and British empires. The U.S., as the primary global powerhouse and reserve currency issuer, must manage its fiscal and monetary strategies prudently to avoid the fate of its predecessors.

The delicate balance between government spending and foreign investor confidence in financing U.S. debt is crucial. If government expenditure surpasses economic growth, it could result in fiscal dominance. In such a scenario, if foreign investors become reluctant to support growing U.S. debt, the government might need to resort to unconventional methods like debt monetization to finance expenses and prevent default.

Drawing lessons from Japan’s experience in recent decades is essential. Since the late 1980s, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has printed money to purchase government bonds, effectively funding government spending by increasing the money supply. This approach resulted in a decade of secular stagnation and deflation, highlighting the risks that central bankers and Wall Street tend to overlook.

Churchill’s prophecy that those who disregard history are bound to repeat it is unfolding before us like a Shakespearean tragedy. In this era of fiscal dominance, it serves as a stark reminder of the importance of learning from past mistakes to avoid similar pitfalls in the future.

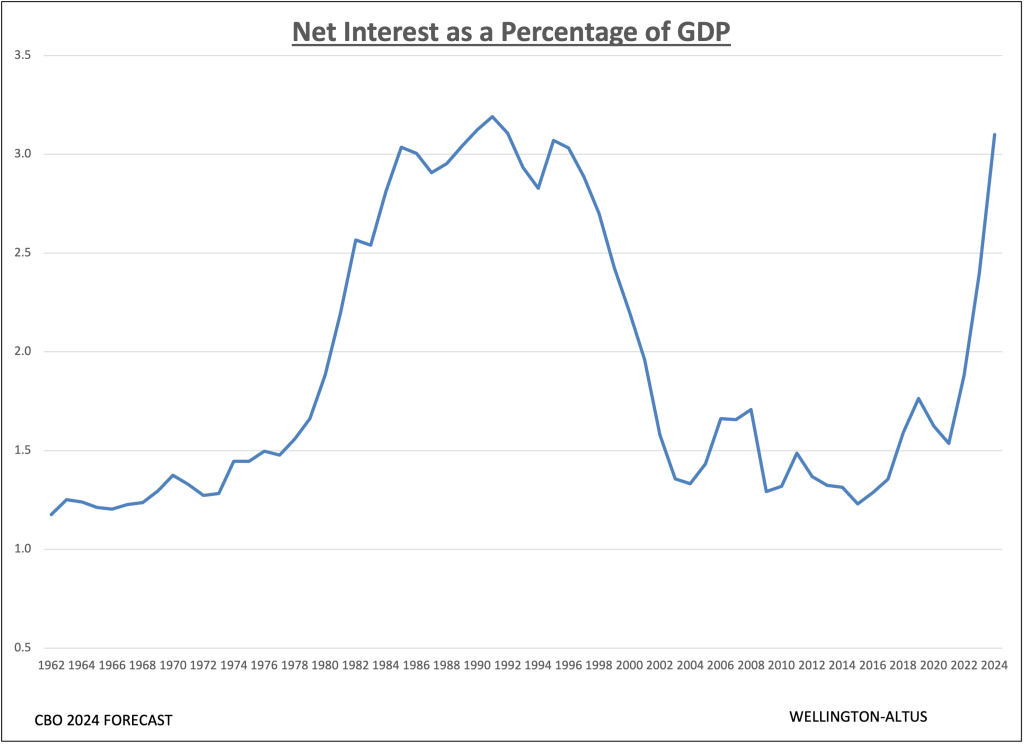

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, the Federal Reserve’s activation of Section 13-3 of the Federal Reserve Act signified a shift toward a more subordinate role relative to the Treasury, with fiscal policy taking precedence over monetary policy. In response to threats of deflation, economic stagnation, and financial collapse, the Federal Reserve might need to keep interest rates low to ensure that foreign buyers continue to finance the U.S. deficit. The Congressional Budget Office’s latest report, which shows interest payments on debt surpassing three per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) and projects a persistent fiscal deficit of six per cent until 2034, underscores the urgency of addressing the deficit—whether through investor financing, debt monetization or spending cuts.  Recent global economic shifts, including the BoJ’s interest rate hikes, China’s economic maneuvers, and the repercussions of sanctions against Russia raise a critical question: who will buy U.S. debt? The real danger lies not in inflation but in the potential failure of a U.S. Treasury bond auction. Over the past four years, my view has been that the Federal Reserve will need to lower rates to forestall a financial crisis, as inflation is not the foremost long-term concern. It has always been true that markets left to their own devices are inherently deflationary.

Recent global economic shifts, including the BoJ’s interest rate hikes, China’s economic maneuvers, and the repercussions of sanctions against Russia raise a critical question: who will buy U.S. debt? The real danger lies not in inflation but in the potential failure of a U.S. Treasury bond auction. Over the past four years, my view has been that the Federal Reserve will need to lower rates to forestall a financial crisis, as inflation is not the foremost long-term concern. It has always been true that markets left to their own devices are inherently deflationary.

We are Out of Options

The spectre of fiscal dominance looms when a government’s financial strategies unduly dictate the central bank’s monetary policy, a situation often precipitated by towering government debt that handcuffs the bank’s efforts to keep inflation in check. This dynamic is playing out as the Federal Reserve endeavors to foster a hospitable climate for foreign investment in U.S. treasuries by suppressing interest rates and managing the dollar’s value. This shift towards fiscal prominence over monetary policy invites scrutiny over the central bank’s ability to simultaneously quell inflation and help finance America’s burgeoning deficit.

The geopolitical situation between Ukraine and Russia has jostled the global economic order, casting shadows of doubt over the U.S. dollar’s hegemony as the primary medium of exchange. The unprecedented measures of freezing another nation’s central bank assets and the spectre of confiscating treasury securities in European vaults are fraught with peril. Drawing from lessons of the past, we must be mindful that the use of the U.S. dollar as a tool of conflict could undermine confidence in the U.S.’s capacity to attract essential foreign investment for its debt.

The urgency for the U.S. to finance a significant portion of its debt—amounting to 38% over the coming two years—underscores the need for strategic actions reminiscent of historical interventions like the Plaza Accord [3]. In a world where global investors scrutinize every potential volatility, and geopolitical dynamics shift with the wind, the appeal of U.S. treasuries could wane. The increasing allure of gold, bitcoin, and some countries’ pivot away from fiat currencies is a testament to the changing tides of investor sentiment.

In a scenario akin to the ‘Dutch Disease,’ where a powerful currency unwittingly erodes the nation’s trade balance and economic diversity, the U.S. finds itself grappling with the consequences. The forward leaning industrial policies rolled out under Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden are aimed at countering this imbalance, but time is needed for these seeds to sprout. The interim puts the onus on the Federal Reserve, which may need to consider reducing interest rates to bolster the economy’s multi-faceted growth.

The U.S.’s reliance on the dollar’s reserve currency status has facilitated a pattern of persistent debt accumulation, a dangerous game that not even Keynesian wisdom could fully safeguard against. As Keynes cautioned at Bretton Woods, no empire, America included, is immune to the pitfalls of fiscal imprudence. Rising concerns over the long-term viability of the U.S.’s fiscal strategy and borrowing habits point to the necessity of a coordinated and calculated response akin to the Plaza Accord of 1985. This could help modulate the dollar’s strength, ensure affordable currency hedging for U.S. Treasury buyers, and reignite the export sector’s vigor.

The Quest for a Soft Landing

The Federal Reserve’s pursuit of a “soft landing”— tempering inflation without triggering a recession—is a tightrope walk between maintaining price stability and fostering economic growth. Cutting the federal funds rate to two per cent might be one step towards bringing the six per cent deficit down to more traditional levels. But we must heed Churchill’s cautionary counsel and recognize that even with a 2.5 per cent GDP growth, a booming private sector is not guaranteed. A paradoxical economic condition, where the private sector suffers a recession amidst ostensibly positive GDP growth, is a distinct possibility.

In 2024, the U.S. faces the formidable task of taming inflation while contending with an anticipated $1.6 trillion deficit. The post-pandemic spending surge has led to significant economic imbalances, and a lack of consensus prevails within Congress and the Federal Reserve on the path forward. The situation’s complexity is compounded by the risk that aggressive rate hikes and liberal fiscal policies may not achieve their objectives, a reminder that not learning from historical fiscal lessons can lead to repeated failures.

In future, the focus should not be solely on the timing of the Federal Reserve’s initial rate cut, but rather on when the yield curve (comparing three-month to 10-year rates) reverts to normal, or smoothly un inverts to bolster the banking system and private sector economic growth. Given the federal funds rate and the length of time it takes for monetary policy effects to materialize, the belief that a single 25-basis point rate cut will spark credit expansion, inflation and economic progress is misguided. A significant rate reduction is necessary to rectify the inverted yield curve to ensure a desired soft landing.

Killing Two Birds with One Stone: A Freely Floating Yuan

Secretary Yellen’s recent visit to China aimed to tackle trade imbalances stemming from its massive production and market inundation with cheaper goods. The simple solution would be market-driven valuation of the Chinese yuan. Allowing the yuan to appreciate would make Chinese exports pricier, thus addressing trade imbalances and curbing overproduction. Additionally, this move could attract foreign investment in U.S. Treasury securities—effectively hitting two birds with one stone.

The idea of China freeing the yuan for unrestricted trade and adopting global GDP measurement standards is gaining attention. It’s a concept that’s been waiting in the wings for over a decade, potentially aligning China with advanced economies without needing agreements like the Plaza Accord.

The elegant yet simple solution of allowing the yuan to float to devalue the U.S. dollar is not currently expected. This move, coupled with the adoption of western GDP accounting, has the potential to usher in an era reminiscent of the post-Second Word War economic boom. It could help alleviate concerns about deflation and secular stagnation, enabling economies to grow their way out of high debt levels. By the mid-1970s, debt to GDP had declined to 37 per cent.

While China has traditionally been cautious about such adjustments, fearing a situation like Japan’s post Plaza Accord downturn, recent economic developments like the real estate bubble burst, may prompt a reassessment.

In a time that calls for structural shifts, investors need to stay nimble and embrace change to navigate U.S. debt refinancing. A freely traded yuan could have a positive impact not only on gold and bitcoin but also on global risk assets, global trade, and Chinese equities. Re-evaluating China’s undervalued stocks in a potential deal could signify a shift. As has been widely said, the true measure of intelligence is the ability to adapt to change.

The 1950s: A Case Study

The 1950s stand out in history as a period marked by fiscal dominance, significant investment in innovation—like the transistor—and strong economic growth. These factors contributed to low inflation and remarkable stock market gains. The S&P 500’s total return soared by 488 per cent from 1950 to 1960, with an annual average growth of over 19 per cent, a performance rivaled only by the secular bull market of the 1990s, which saw an 18 per cent annualized return. The 1950s represents an overlooked robust bull market era.

Reflecting on this historical period, we see parallels in today’s landscape of fiscal dominance, where government spending significantly influences economic direction. The U.S. faces the dual challenge of preserving its currency’s value while promoting economic growth, and it must draw on past experiences to adeptly maneuver through the complex interplay of fiscal and monetary policies.

In summary, the 1950s offers valuable lessons for current policymakers tasked with fostering innovation, managing debt judiciously, and ensuring economic stability. This era demonstrated that fiscal dominance need not impede economic growth and innovation; rather, it can complement them. By embracing these historical lessons, the U.S. can avoid the pitfalls that have ensnared former empires and set a course for sustained prosperity.

Investment Strategies for Today’s Economic Climate

In an economic climate resembling the 1950s, risk assets such as the S&P 500 have historically shown robust performance. This is evident in the often-overlooked bull market of that decade. Despite present uncertainties— volatility, innovation, demographic shifts, and global conflicts—1950s trends could re-emerge.

Objective evaluation of current economic data—tax revenue, full-time employment growth, and sales figures—indicates that the private sector may be decelerating. A 2.5 per cent GDP growth rate does not necessarily reflect a thriving private sector. The perceived economic expansion might be superficial, buoyed by extraordinary government outlays, rather than indicative of the private sector’s vitality. As such, conventional assessments of the economy’s health warrant scrutiny.

Post-pandemic, the U.S. economy is operating to a new beat, rendering the Federal Reserve’s traditional economic tools outdated. Current fiscal policies are central to stimulating demand and shaping business cycles, as evidenced by Congressional Budget Office predictions that the budget deficit will hover around six per cent of GDP until 2034. The economy’s path will hinge on the sustained and effective application of these fiscal measures. Independent of political leadership, the U.S. is likely to persist with its industrial policy direction, which could lead to scaled-back fiscal spending and modest growth. Nevertheless, lower interest rates could foster an environment conducive to private sector expansion.

Globally, we are in a phase of reflation, with central banks reducing rates and alleviating concerns about inflation. By the end of 2025, the federal funds rate is predicted to level off at close to 2.5 per cent. It is a misconception that the global economy can withstand high interest rates without inciting a financial crisis. My projection for the S&P 500 by the end of 2025 is 6,000. Should it surpass this benchmark prematurely, it may signal an excessively optimistic market, necessitating strategic recalibration. The demand for gold and bitcoin is likely to remain robust, and oil to trade between $70 and $90. Predictions suggest a decrease in fiscal expenditure and interest rates, mirroring the patterns of the 1950s. It would be wise for investors to favour companies with steady growth, as the difficulties faced by cyclical businesses have shown up in their earnings reports. Investors should concentrate their attention on leading companies the “winners” of the current era.

In the words of Sir Winston Churchill, understanding historical patterns is essential to navigating the present economic challenges and seizing opportunities effectively.

[1] In 1948, during a speech to the House of Commons, Churchill paraphrased philosopher George Santayana and said, “those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” This quote has been widely associated with Churchill ever since. [2] Fiat currency: government issued currency that is not backed by a commodity (such as gold). [3] Plaza Accord: 1985 agreement between France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States to correct trade imbalances by depreciating the U.S. dollar compared to the yen and deutsche mark.