When it comes to estate planning, co-ordination of documents and details such as beneficiary designations matter. A lack of planning and out of date or incomplete documentation can result in additional costs, delays and taxes for your estate, or a loss of control over certain aspects, such as the guardianship of minor children and/or how you want your assets to be distributed when you die. Even carefully planned estates can be undone by technical glitches or unnecessary complications.

What is an estate1?

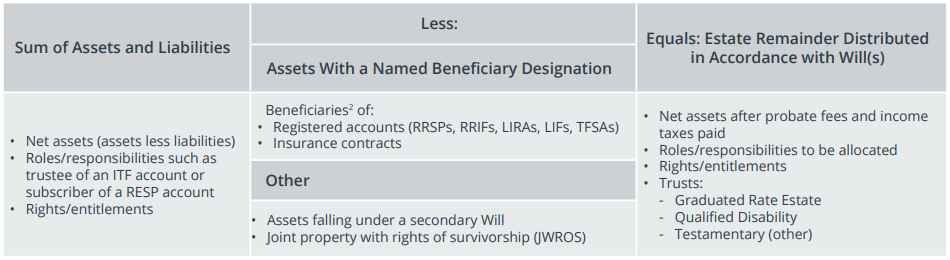

An estate is the net worth of a person, namely: the total value of your assets, including any legal roles, responsibilities, rights, and entitlements you may have, minus assets flowing directly to your beneficiaries and any changes to your legal standing, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: The Estate Equation

Your Wellington-Altus investment accounts

When you die, the assets in your various Wellington-Altus accounts remain invested until they are transferred to beneficiaries named in the account documents or your executor acts on the instructions you have provided in your Will.

Upon notice of death, purchases in non-managed accounts are restricted, dispositions are allowed and any outstanding or closing fees will be charged. There are no trading restrictions on managed accounts and fees will be charged until assets are transferred and the estate is settled.

To facilitate the transfer of wealth, here are some key estate planning points to consider:

- Rollover opportunities. Many registered accounts, including RRSPs, RRIFs, LIFs and TFSAs allow for assets to be “rolled over” to a spouse, minor dependent or disabled dependent without tax consequences on the death of the account holder.3 It is possible to opt out of the rollover if desired.

- Minor and adult beneficiaries who lack capacity. Include the name of a trustee to ensure that they can access funds for the care of dependant beneficiaries.

- Legal standing. A spouse is typically the legal beneficiary of a locked-in registered account. Ensure that separation or divorce notices, or a waiver to name a different beneficiary, are on file as required.

- Jurisdictional wrinkles. Legislation related to naming a beneficiary and the rights and entitlements of spouses and common-law partners can vary significantly across different provinces and territories. In Quebec, registered accounts do not allow beneficiary designations. Common-law partners do not have the same rights as spouses in all jurisdictions and may have no rights at all to the estate. As well, in the absence of a Will – an individual’s estate is intestate – spouses and children may not automatically inherit all assets.

- Joint ownership. Holding property and accounts jointly with rights of survivorship is a popular tool to bypass probate, particularly in jurisdictions with high probate fees. There are many potential traps with this sort of planning, and it should only be undertaken with the advice of an estate planning professional.

Note that with JWROS, tax and succession law do not always align. If one owner dies, for example, assets will transfer to the surviving owner, but the deceased is still considered to have disposed of the assets and their estate may be taxed depending upon who the surviving joint owner is. For JWROS accounts where the owners are not spouses or common-law partners, as in the case of an adult child being added to a parent’s investment account, it’s important to document the intention of this arrangement to avoid legal issues when settling the estate, as it may be used to transfer assets or simply for administrative purposes.

Estate Planning in Practice: A Case Study

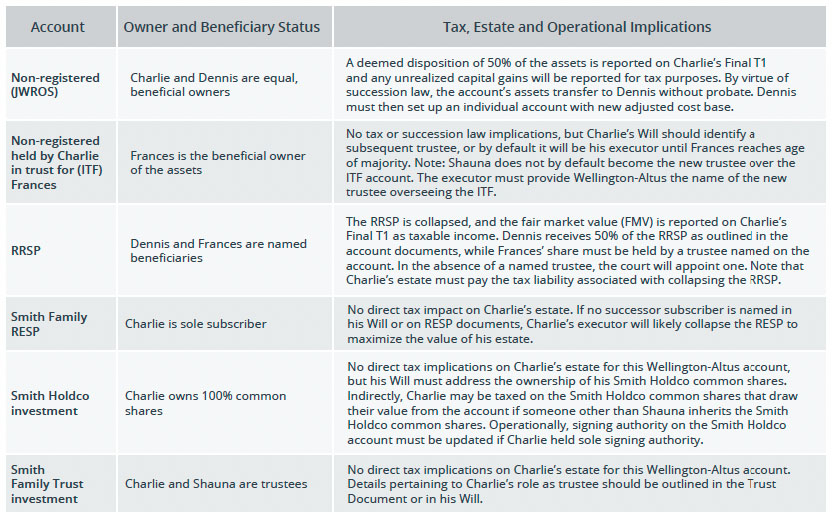

Charlie and Shauna Smith are married with two children, Dennis, age 20 and Frances, 16 and live in Saskatchewan. What would happen to Charlie’s Wellington-Altus accounts if he dies?

The Power of 5

It’s wise to revisit your estate plan at least every five years and when one of the following life events occurs:

- A change in your relationship status. A new common-law partner or spouse, a relationship breakdown or the death of a common-law partner or spouse.

- The purchase of real property.

- A new beneficiary or new beneficiary need. The addition of a child, grandchild or other dependent, or when a beneficiary has additional needs to be addressed.

- A change in residency. When moving to a different province/territory or country.

- A significant change in your health, financial or other economic circumstances.

Your advisor can help

There is no better time to begin the process of estate planning than today. Reach out to your Wellington-Altus advisor for assitance to begin the process.

1 Under Quebec’s civil law, this is known as a person’s patrimony or succession.

2 Beneficiaries may be named at the account level or in the will. Beneficiaries cannot be named on registered accounts in Quebec.

3 Beneficiaries to registered accounts cannot be named in Quebec. This intention must be included in the Will.