Economic Squid Games: China’s Enduring Mastery of Survival

Download this article as a PDF.

“We’ve already come too far to end this now.”

– Sang-Woo, Squid Game

Squid Game is a dark drama set in Korea that depicts the lengths some individuals will go to in order to try and eliminate their extreme levels of debt. Today, we see many countries facing a similar dilemma: decades of strong nominal GDP growth once reduced debt-to-GDP ratios to sustainable levels, but slowing growth has led to a new awakening. Nowhere is this more evident than with China, whose recent troubles with Evergrande have thrust them back into the headlines.

We suggest that the Evergrande episode has confirmed a new phase in China’s evolution and a transition is now underway. Chairman Xi has already acknowledged the need for structural change, signaling to some investors that he has accepted that he can procrastinate no longer. A new era of “Common Prosperity” has begun, and investors should take note. We suggest that China will remain a “Crouching Dragon”1 as it implements new policies to facilitate the expansion of credit, which will occur in a more deliberate and nuanced fashion to generate higher-quality and balanced growth in China. In Squid Game, there will be winners and losers: some of the highly indebted players become stronger as they survive the physical and psychological twists needed to advance in the games – perhaps a fitting allegory on the enduring strength of China as we look forward.

First: A Brief Lesson in History

The 100th anniversary of the China Communist Party (CCP) was held on July 1st this past summer. Yet, many of us may not remember that at the end of WWII, the West largely ignored China’s significance. In 1949, the CCP declared China’s “independence,” an event that was met in the West with bitter recriminations and conflict over who was responsible for that loss. This was because the “loss of China”2 had major geopolitical and economic consequences. Many western businesses had worked in China for extended periods positioning their business models in anticipation of a post-WWII capitalist China, all of which was lost. Imagine a world in which China was an open and democratic economy driven by market forces since 1949: Would there be concerns about an invasion of Taiwan? Would there have been a Vietnam War?

Even until the 1970s, the U.S. continued to recognize the Republic of China, located in Taiwan, as China’s true government. Two decades after the “loss,” Richard Nixon reversed course and began negotiations with the People’s Republic of China, and the opening of China began. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping drew on former Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP), which had saved the Soviet Union from early collapse in 1922. He emulated Lenin by moving the CCP toward a socialist market economy under communism, but with Chinese characteristics. What Deng Xiaoping offered to the West was a market with one-fifth of the world’s population.

The Myth of Asia’s Growth

China has become an economic superpower largely because it capitalized on its sheer size. Yet, it is following the natural evolutionary process that all countries must follow to become an advanced economy. After decades of neglect under Mao, and with its acceptance into the World Trade Organization in 2001, China entered into a period of rapid growth. In the early phases, the country used its labour cost advantage and decades of infrastructure neglect to develop an economy based on manufacturing exports, urbanization and fixed investments. This phase of credit-fueled growth, typical of developing nations, generated the unbalanced growth and overcapacity we see today. As with any developing nation, this growth cannot last forever and typically ends in a credit crisis.

China is not unique in its evolution. It is, however, unique in the size of its credit bubble, which, if popped, could generate major global consequences. Economist Paul Krugman’s “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle,” written two decades ago, saliently argued that Asia’s seemingly dynamic economies, upon closer inspection, displayed “startlingly little evidence of improvements in efficiency.”3 Their growth relied instead on rapidly increasing inputs, capital and investment. According to Krugman, there was nothing miraculous about Asia’s economic growth. It mirrored the incredible growth rates seen in the Soviet Union after WWII.

Curiously, Krugman also pointed out that when measuring the growth of the Soviet Union, GDP was calculated differently – ironically as China does today. The Soviet Union focused on inputs – not outputs, as the West does. Not surprisingly, Xi gets it: the Chairman often makes distinctions between fictional and genuine growth. China does not have free capital flows in and out of the economy and is now dependent on foreign inflows of capital to support growth.

In China, the RMB is fixed to the USD. Is it overvalued or undervalued? One thesis often put forward is that the Chinese economy is not as big as consensus believes due to its currency being significantly overvalued. Let’s not forget that in the 1980s when the simple assumption of calculating the (Soviet) CCCP’s4 GDP followed western conventions, policymakers realized that their economy was actually much smaller. This was because the CCCP was spending a vastly larger percentage of its GDP on military expenditures, motivating the Reagan administration to accelerate the arms race in an attempt to bankrupt its cold war adversary, at which they succeeded.

Transformation: Xi’s Vision of Common Prosperity

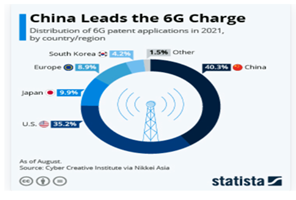

China understands its need to transition. It has fiercely built up its capabilities in innovation and technology to ensure it maintains its global stronghold, just as the Soviet Union recognized that technology was key to maintaining power in the 1950s.

And, yet, China’s recent crackdown to declare bitcoin illegal – even as it held the global market position in bitcoin mining – is an example of how planners have a distinct idea of how China will evolve. While this may have appeared perplexing to some, it supports China’s new direction. Cryptocurrencies reduce the power of centralized governments. China already has a central bank digital currency (CBCD) well under development. And, bitcoin mining has increased income disparity, blatantly contravening with China’s new commitment to Common Prosperity.

What is Common Prosperity?

Common Prosperity takes China back to its socialist roots by seeking to achieve prosperity across the masses by narrowing the wealth gap. Common Prosperity is not a new ideal in China. In fact, it was first introduced by Mao Zedong in the 1950s, and then repeated by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s when he modernized an economy devastated by the Cultural Revolution. Today, Xi has indicated that it is core to the governing foundations of the CCP, focusing efforts on cracking down on excesses to eliminate poverty. The government is taking action to curb tax evasion, using taxation and other income redistribution levers, as well as encouraging charity and donations.5 As well, Beijing is following the rest of the world in what may be long overdue: reigning in large tech giants to try and eliminate the monopolistic power that they have largely assumed.

The ultimate end goal? Xi wishes to achieve economic rebalancing to move toward more consumption-driven growth and to reduce reliance on exports and investment. By spurring domestic demand, as well as continuing innovation, the Chinese can become more self-reliant as a nation.

Many Challenges Ahead

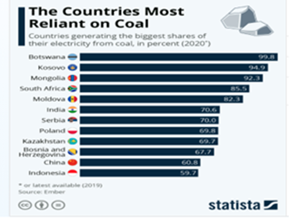

The transition will not be an easy one. China still lacks the infrastructure to support an advanced economy. China is rich in coal, which continues to be its main energy source. To be clear, many emerging markets still rely on coal as their main source of energy. Yet, the proportion of coal in the energy consumption structure has fallen to 56.8% in 2020 as the world moves toward greener alternatives. In order for China to be seriously seen by the rest of the world as an advanced economy, China recognizes that it must find new green energy sources, but this will take time – it cannot be accomplished overnight. At present, the cumulative installed capacity of hydropower, wind power and solar power in China ranks number one in the world. However, wind power and solar power are volatile and intermittent.

Like many nations, China is turning to nuclear power as a solution. However, as the energy crisis in Europe has shown, transitioning to a net-zero green economy takes time. Mismanagement of this transition phase by policymakers is a risk that investors must put on their radar. We have suggested that the irony of the goal of achieving net-zero is that it will be commodity intensive and thus may result in a commodities supercycle. Yet, investors need to accept that there will also be risks during this transition period.

As Evergrande reminds us, China’s future growth cannot be reliant on the property market. Until recently, real estate had comprised almost 30 percent of China’s GDP. This was largely supported by the belief of sustained growth that came with the urbanization of such a large population. However, China now faces a demographic problem. With an increasingly aging demographic, and the now-evident consequences of its one-child policy that lasted from 1980 to 2015, the population is shrinking. As such, even if the credit excess is successfully contained, the demographic situation brings new headwinds that are likely to result in slowing growth and a slowing property market.

Where to for Investors?

The adjustment period is expected to be a precarious one. Yet, we should not be surprised by Xi’s policy moves. China understands its need to embark on a long journey in order to evolve into an advanced economy. To be clear, China’s policymakers are students of history and have always played the long game.

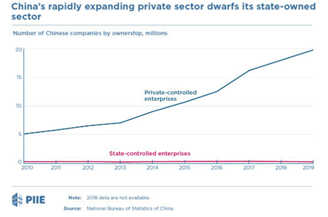

Despite the alarmist views to hit the headlines about Evergrande over recent weeks, we suggest that the sky is not falling. Outside of the property market, there are few signs of contagion. In fact, China has a robust and growing private sector that has almost quadrupled over the last decade.6 Those private technology companies hit by regulatory tightening over the past year only make up a very small proportion of the entire private sector, which continues to innovate, strengthen and grow.

However, investors do need to take a nuanced approach when investing in China. The tide has turned and the previous gains that manifested themselves in ETFs and other passive index products will not be easily repeated in the future. We have entered into an investing era in which a nimble approach and thoughtful analysis will benefit investors – this is a stock picker’s market. A recent Chinese government bond sale confirms that many foreign investors continue to maintain confidence in the China opportunity, as they should. Over three-quarters of investors in the 30-year bond issuance, the longest maturity, were from outside of Asia.7

China has used the shock of the Covid-19 pandemic to begin a new era of economic growth, no different than its decision in 1949 to reject capitalism and democracy. As Squid Game forces us to confront the impact of capitalism on modern society, which has driven excessive debt levels in individuals, it may be mirroring the situation we see today with many nations globally. Like China, Gi-hun, the last man standing in the Squid Game, reminds us to never underestimate the human drive to endure, to overcome and to ultimately win.