“The holy fool is a truth-teller because he is an outcast. Those not part of the existing social hierarchy are free to blurt out inconvenient truths or question things the rest of us take for granted.” – Malcolm Gladwell in Talking to Strangers

Since 2020, I’ve been one of the few holy fools that put forth the thesis that aggressively raising rates into a highly levered global economy would result in another financial crisis. My sin was questioning aggressive rate hikes based on the belief that low unemployment causes inflation. In the early days, Wall and Bay Streets met my thesis with disdain. Then the Bank of Canada paused. But now, after the events of recent weeks and the banking crisis in the U.S. and Europe, it looks like the inconvenient truths have come home to roost—again. Consensus quickly pivots with attempts to impress by going down rabbit holes and presenting the situation as a complicated maze of unforeseen events. But what happened is basic Banking 101. Let me explain.

The image of a bank run has been used many times by Hollywood. In Frank Capra’s holiday classic, It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), the hidden lead is how a family’s financial fate depends on the bank’s soundness. George Bailey sacrifices his desire to travel the world to run a small community bank in Bedford Falls with a mortgage business. The forcing function in the narrative is a clerical mix-up that manifests into a deposit run. The classic line delivered by Jimmy Stewart is “the money is just not there,” and results in the subsequent use of his own money—money intended for his honeymoon—to stop the institution from dissolving. In the end, the community saves itself. Today’s bank crisis is based on the same basic principle that nasty things happen when deposits rapidly leave a bank. With the Federal Reserve continuing to raise rates, investors should expect the pace of deposit withdrawals to accelerate, tightening credit conditions and increasing deflationary forces. But a happy ending is still possible, just as it was in It’s a Wonderful Life. The credit and currency market is interpreting the recent action by the Fed as the dovish pivot so many have been waiting for.

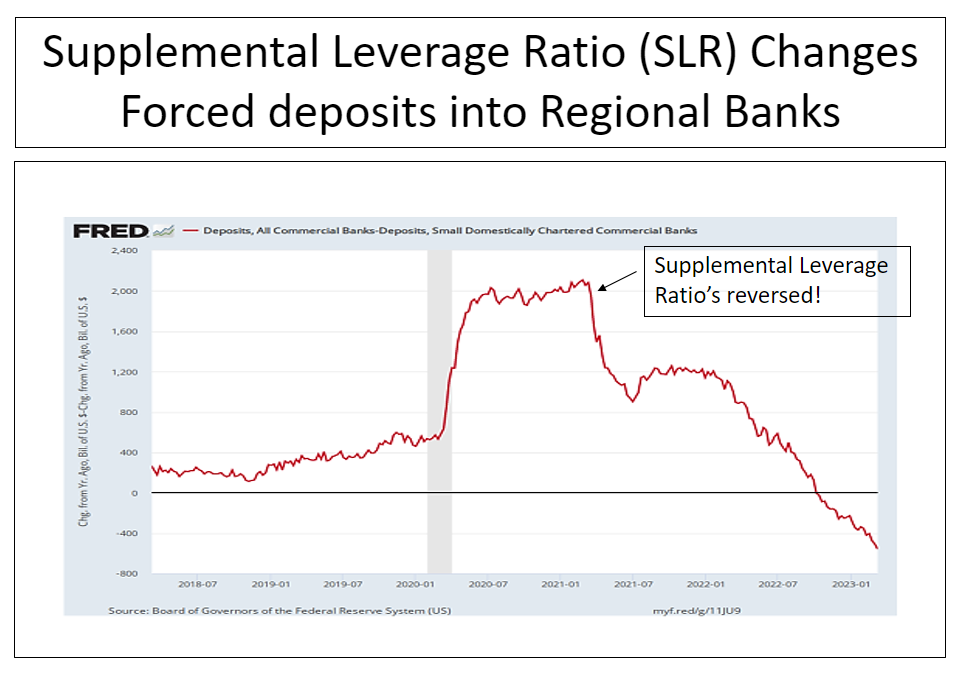

An oversimplification of our current predicament starts with responding to the COVID-19 crisis when the Treasury and Federal Reserve worked together to ensure the financial system had enough liquidity. The U.S. federal government began massive debt-financed spending. In March 2020, President Trump signed the $2.2 trillion Economic Stimulus Bill, the CARES Act or Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, into law. Then, in March 2021, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act, which contained $1.9 trillion more in relief. Finally, in April 2021, another trillion or so of COVID-19 relief arrived in the Consolidated Appropriations Act. These programs created massive new deposits in the banking system and rules were changed to ensure the financial system could handle the influx. [1]

In early 2021, the Fed concluded that the crisis was over, reversing the regulations and creating an environment where deposits left the big banks and flowed to regional banks. With a massive inflow of deposits and no loan demand, the regional banks invested deposits in government securities at very low interest rates.

Fast forward to 2022, and the Federal Reserve embarks on the most aggressive rate-tightening cycle in modern history and begins to drain reserves out of the system (Q.T.). Bonds experience their worst year of performance since 1777. For regional banks, deposits start to leave, and their investment portfolio market value significantly declines. Shifting of deposits to money market funds accelerated when the Fed funds rate breached 4%. Deposits in money market funds are considered as outside of the banking system. To maintain their Tier 1 capital ratio, regional banks sell investment securities at depressed market prices instead of holding them to maturity as planned. As a result, banks start to breach their Tier 1 capital levels, which requires a capital raise and lights the fuse of our current banking crisis in the regional banking sector.

With financial regulators trying to ring-fence the bank crisis such that it stays isolated in the regional bank sector, the recent events have yet to metastasize into a credit event like 2008. Investors should heed what the currency and credit markets say—that the Federal Reserve will pause and cut rates sooner than many expect. The irony was that one of the consequences of the 2008 GFC was that companies were dissuaded from owning near-cash instruments and thus kept it in bank accounts earning little or no interest. With interest rate differentials at such extremes, and the regional banking crisis, the pendulum swung back the other way. Credit conditions will tighten, precisely what the Fed wants.

Financial regulators are working hard to contain the latest banking panic. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada, and several major central banks announced a coordinated effort to boost the flow of U.S. dollars through the global financial system. Jamie Dimon, J.P Morgan CEO, is leading an industry effort to have Wall Street bail itself out, just as Mr. J.P. Morgan did in the 1907 banking crisis. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced a de facto guarantee of all $17.6 trillion in U.S. bank deposits. Regional bank stocks rallied, but it’s essential to understand what this moment means. This does not explicitly guarantee all deposits, but it may be close enough to ring-fence the problem. Dodd-Frank lets the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. guarantee uninsured deposits under its “systemic risk” exception. But banks must first fail for the exception to apply, and the systemic risk is supposed to be genuine. In other words, if a bank gets into trouble, then and only then will the process kick in and a determination be made on whether depositors will be saved.

The key point is that even if deposits are implicitly guaranteed, the incentive to capture higher interest rates in money market funds will force deposits out of Regional Banks.

My conclusion is that deposits will continue to leave until interest rates in regional bank chequing accounts increase, or the Fed dramatically cuts the Fed funds rate. In any event, credit conditions are tightening, and this is deflationary. What rational investor would keep significant money in a bank deposit earning next to nothing when you can make 4.75% in a money market fund? Incentives drive people, and the Federal Reserve’s recent interest rate hike only worsens this matter. The US economy just experienced a deflationary exogenous shock. As a result, we should expect credit creation to contract, deflation to accelerate, and growth to slow … all the conditions needed for the Fed to cut. But is it the end of the world? No.

What Should Investors Do?

The Fed continued to raise rates until something broke, and it did. The rapid response by policy makers should isolate the crisis to the regional banking sector. However, additional failures cannot be ruled out. We expect deposit flight to accelerate with flows into high-yielding money market funds. A banking crisis caused by duration risk and the lack of interest rate hedges is different from what we experienced in 2008. Credit and currency markets are now signaling our non-consensus view that the Fed funds rate and the Bank of Canada overnight rate will be cut in the back half of 2023. We expect economic data to continue to slow and strong evidence that the Fed is making substantial progress in its fight against inflation. With the banking crisis contracting credit creation and being deflationary, the Fed will not have to raise rates as high as they previously expected.

To be clear, central bankers are still data dependent. Still, eventually, their lagging old backward-looking year-over-year data will reflect what the more modern real-time forward-looking data has been saying since late 2022, that a new era of slow economic growth and disinflation is upon us. The peak in interest rates is in: buy bonds. The rate of decline will depend on how rapidly inflation falls. My call has always been that the Fed funds rate and the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate will be between 2.5% to 3% by late 2024. We are also past peak inflation. Equity markets show that technology, a long-duration asset is the place to be. Until proven otherwise, the bear market low was in mid-October 2022. As Mr. Buffett suggests, “be greedy when others are fearful.” However, this is no time to be a hero. Instead, focus on high-quality large cap companies with solid management teams who can grow their business in a slow- growth disinflation environment. I’m still holding onto my view that markets will travel down the same path taken in the 1994-95 episode. With some luck, we will look back on this episode and say it was easy, as a great buying opportunity for those who took advantage. But it’s never easy.

[1] The Supplementary Leverage Ratios (SLR) were relaxed.