What if the U.S. Government Defaults on its Debt?

If the U.S. was to default on its debt obligations, it would cause investors to flee from U.S. Treasuries, leading to a decrease in confidence in U.S. government debt and the U.S. Dollar (USD) as being the medium of exchange for the global economy. In turn, this would negatively affect other markets— interest rates would increase, making borrowing money and purchasing other investments more costly. In addition, a decrease in confidence in U.S. government debt would also lead to extreme volatility in the global capital market akin to the 2008 global financial crisis. The long-term effects of debt-ceiling debates are that inflationary expectations are kept well anchored.

As Nobel Prize-winning economist Thomas Sargent suggests, “persistent inflation is everywhere and always a fiscal phenomenon.” Simply put, debt-ceiling debates help ensure that inflation is kept in check. A current study from the St. Louis Federal Reserve concluded that fiscal policy added 2.6 per cent to the level of inflation in the U.S. and 2.3 per cent in Canada. In an environment where many have wrongly concluded that inflation is caused by the private sector and low unemployment—and not supply shocks or fiscal policy— ensuring that checks and balances like the debt-ceiling debate are in place, will help keep inflationary expectations well-anchored close to two per cent.

The U.S. government will not default on its debt. The simple reason is that it has a monopoly on printing U.S. dollars (USD). Despite political gamesmanship and the concerns put forth by many, given the extensive level of debt and spending that the U.S. government does, it has never defaulted on its debt—even during times of economic hardship such as the Great Recession. Additionally, although it can produce new money, it is prudent that the U.S. government monitors debt levels to ensure confidence in the soundness of the USD. While in theory, there could be replacements for the USD as the medium of exchange in the global economy. Ultimately, the U.S. government will not default on its debt when it has a monopoly on printing U.S. dollars so long as the global economy has confidence in the policymakers in Washington, D.C. and Wall Street, and the U.S. maintains its innovative and technological leadership— which we don’t see changing.

Keynes’ Warning at Bretton Woods

At the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, British economist John Maynard Keynes warned the U.S. about its massive wartime borrowing—a looming debt crisis could have catastrophic effects on the global economy and push the world back into a depression. The fears of deflation and secular stagnation of the 1930s were at the forefront of everyone’s mind. Keynes was quick to point out that although the end of the war created some much-needed optimism, the economic conditions of the day presented a significant challenge. He told conference delegates that the vast amount of past borrowing and the vast amount of future borrowing could not be conceivably met by taxation without plunging the world into a deep depression.

The cause of Keynes’ fear was rooted in the fact that the U.S.—the world’s largest economy—had racked up massive amounts of debt during the Second World War, with much of the money borrowed from foreign investors. With all the money owed to foreign banks, Keynes warned that the U.S. would have to confront an “ensorcellment” of debt which would only become more and more challenging to pay off. In addition to the looming debt crisis, Keynes also warned that the monetary system at the time—based solely on the gold standard—was becoming antiquated and unable to manage world financial markets effectively. One of the primary reasons he proposed the creation of the International Monetary Fund, the Bank of International Settlement, and the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development was to create a more flexible and secure global finance system. Almost 80 years later, these institutions, and the place of the USD as the medium of exchange of the global economy, are being challenged. Keynes also suggested that Central Banks should seek to maintain low interest rates to stimulate economic growth and avoid pushing countries into debt. He said that international cooperation and better economic coordination were essential to prevent a debt crisis.

Debt Levels Today

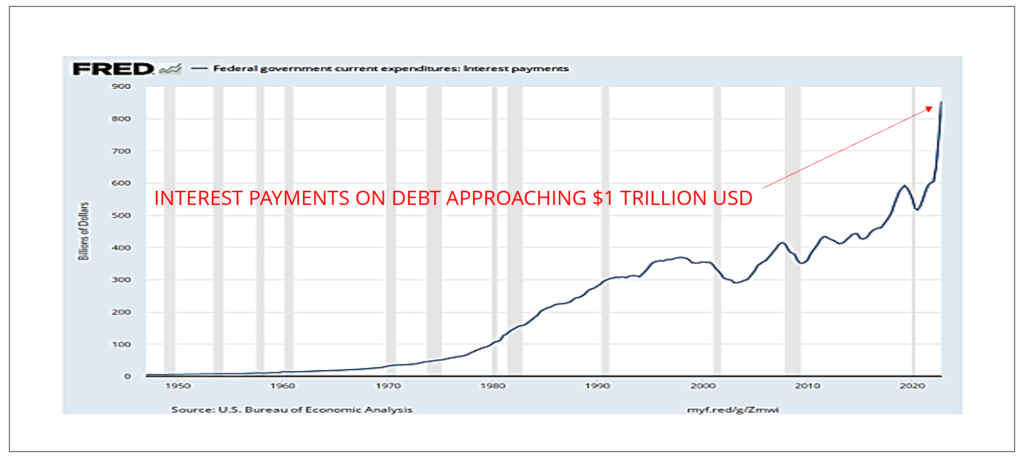

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, debt levels are at an extreme. With the rapid rise of interest rates by the Federal Reserve, interest payment on the U.S. debt is equivalent to the defense budget. More specifically, if the Federal Reserve continues to raise rates, interest payments on U.S. federal debt will eventually top $1 trillion. Ultimately, Keynes’ caution at the Bretton Woods Conference proved prophetic. In the ensuing years, the U.S. did begin to experience a significant debt crisis, which necessitated a series of measures to deal with the problem. To wit, the debt-ceiling crisis so many are concerned about today, has been with us since the end of the Second World War. And through all the turmoil that has followed, the U.S. capital markets are the deepest and most transparent in the world, and the U.S. leads in innovation and research. True: deficit spending needs to be kept in under control. True: long-term inflation is mostly a fiscal policy problem, not a monetary problem. True: there will be a high degree of contentious political deception. But in the end, a deal will be made and the government will pay its bills in a non-inflationary way. Investors should view any market dislocation as an opportunity to accumulate shares of high quality assets that may temporarily go on sale.

Debt Ceiling: A Short History

The debt-ceiling is a legislative limit on the ability of the U.S. government to borrow money from the public. It usually takes the form of a statutory limit set by Congress on the amount of money the U.S. Treasury is allowed to borrow. It does not limit spending, merely how the U.S. Treasury can finance it. It has become a topic of debate in Congress, with many arguing that the debt-ceiling should be raised. In contrast, others say that the government should reduce deficit spending instead. It is one of the more politically charged fiscal debates.

Debt ceilings first appeared in the U.S. in 1790 when the First Congress created a maximum level of $75 million to fund the operations of the newly formed U.S. government. This cap on total debt, which was increased periodically by Congress over the years, was intended to ensure that the government could only borrow money within certain limits, thereby preventing it from going too deeply into debt. By 1917, the First World War had pushed the debt limit above $12 billion, a number that Congress could no longer efficiently manage, so the modern budget discipline system was created. In addition to creating the debt ceiling, Congress also established a spending ceiling with war and the demands of British creditors in mind. This allowed Congress to set a level of government spending each fiscal year, with any spend above this figure requiring Congressional approval. This meant that any bill that increased spending had to be voted on through Congress.

The debt-ceiling has been used to both ensure that the U.S. government can fund its operations and to limit its borrowing, but it has also been used as a political tool. In recent years, disputes over the debt-ceiling have intensified, with Republicans and Democrats frequently at odds over how large the ceiling should be and whether it should be raised. The political nature of the debate has meant that the debt-ceiling has been a contentious issue, with no clear consensus on its implications or how it should be handled.

Recent Events

Since 1995, the U.S. has experienced numerous debt-ceiling crises. Each one has had different levels of effect on the stock market. Generally, the stock market has reacted to the debt-ceiling crisis with short-term uncertainty and volatility. Over the long run, however, the market seems to recover, often with positive returns.

In October 1995, the U.S. federal government shut down due to a budget impasse between Congress and President Clinton over the national debt limit. The shutdown lasted for more than two weeks and immediately impacted markets—stock prices initially dropped for four straight days. The day after the shutdown began, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 62 points, the Nasdaq Composite Index dropped 2.1 per cent, and the S&P 500 dropped 1.1 per cent. Over the next week, the S&P 500 dropped an additional 3.3 per cent. However, the markets soon regained their composure. By the end of the crisis, the Dow had gained 20 points, and the S&P 500 had recovered its losses and ended the month slightly up. In the longer term, the crisis had even less of an effect. Over the next year, the Dow increased by 8.5 per cent, and the S&P 500 rose by 17.5 per cent.

2011 USA Downgrade: A Closer Look

In August 2011, a more significant debt-ceiling crisis occurred. Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating for the first time in history, causing stock prices to fall significantly. The Dow dropped 635 points the day after the downgrade, and the S&P 500 dropped 6.7 per cent. Over the following months, the markets continued to decline. The period around the debt-ceiling crisis saw the Dow fall four per cent, and the S&P 500 falling nine per cent. However, the market soon rebounded. Overall, the stock market has responded to debt-ceiling crises with uncertainty and volatility in the short term. However, the long-term effects seem minimal, and the market has often quickly recovered. At the end of 2011, the S&P 500 total return was 2.11 per cent, and the Nasdaq 100 was 3.61 per cent.

2013 Obama Vs. Congress: Round 2

By the end of 2012, the U.S. had reached its statutory debt limit of $16.394 trillion. This limit was achieved due to government spending, including a decrease in tax revenue and the implementation of stimulus spending after the 2007-08 financial crisis. The 2013 crisis culminated in a 16-day government shutdown in October 2013. The debt limit was eventually raised as part of a deal between the White House and Congress that also included a reopening of the federal government at reduced spending levels, thereby avoiding default on U.S. debt payments. This debt-ceiling crisis became a major source of uncertainty and market volatility. From May to June 2013, the S&P 500 index fell by 5.8 per cent in anticipation of the debate and negotiation surrounding the debt ceiling. During the same period, the 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield dropped by nearly 50 basis points, signifying a sharp decline in investor confidence. But after the dust settled, the S&P 500 total return for 2013 was 32 per cent, and the Nasdaq 100 total return was 38 per cent—reinforcing our thesis that the short-term volatility the debt-ceiling crisis provides investors, is an opportunity.

What Should Investors Do?

Equity markets tend to have a 10 per cent correction every year. Those that prepare for such an event, take advantage of buying high-quality assets that are on sale. A debt-ceiling volatility event may very well happen in 2023, providing the excuse of short-term market correction. That said, never underestimate the ability of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and President Biden to cut a deal. Our bullish view of the equity markets in 2023 is predicated on the fact that the era of fiscal policy adding to inflation is over. The debate over the debt-ceiling should provide much needed fiscal restraint, which should help inflation continue its long march down to the desired target of the Federal Reserve. We continue to disagree with consensus and suggest investors should continue to position for a good year for risk assets.