A Secret War to Control the Fed?

The Danger of Bowing to Political Pressure

With the recent pivot to a highly hawkish stance by the U.S. Federal Reserve — despite the data suggesting the need for continued patience — is the Fed bowing to political pressure? As legendary football coach Bill Parcells reminds us, “you are what your record says you are.”

Aggressive interest rate hikes and tightening run the risk of pushing the economy into a recession and, if not carefully managed, the potential for an ensuing financial crisis. Anchoring to the post-WWII era provides the best guide for central bankers. In that period, the record for the Fed navigating troubled waters was good.

Is the Fed on the verge of making a policy mistake?

Author Michael Lewis reminds us of the consequences that can emerge when independent bodies succumb to political pressure. In his latest book, The Premonition, he suggests that the politicization of the CDC contributed to the ultimate mistakes that prolonged the Covid-19 pandemic. Lewis likens this to how the University of Texas Longhorn football team consistently ranked higher at the start of the season than at the end. With its vast resources, access to talent and sway with voters who determined the rankings, the Longhorns symbolized the U.S. at the start of the pandemic — well-positioned for success. Yet, when the game was played, its leadership failed to produce the expected results. As legendary football coach Bill Parcells once said, you are ultimately judged by the result: “you are what your record says you are.”

In its most recent communication, the U.S. Federal Reserve has once again pivoted to a highly hawkish stance, suggesting imminent and aggressive rate hikes. Many pundits are now emphatically proclaiming that persistent inflation has been caused by monetary policy and is cyclical in nature. Why this pivot? With the data suggesting that continued patience is needed, perhaps the Fed is bowing to political pressure in this mid-term election year. Yet, a new willingness to implement extreme policy measures creates the risk of a recession and — if not carefully managed — the potential for an ensuing financial crisis.

Why the Pivot? The Data Continues to Suggest Otherwise

Lewis’ thesis suggests that thought leaders are not brought into the decision-making process and are, more often than not, marginalized by the political infighting within an organization. We may be witnessing this today with the latest central bank communication.

Today’s consensus view on inflation has been predicated on the belief that we are experiencing a year-over-year increase in the general price level. What is consistently overlooked is the component of price changes that are relative due to the exogenous shocks of Covid-19 and war. While many pundits now argue that quantitative easing (QE) actions, largely directed by the western world, have caused inflation, what undermines this stance is that the inflation we are experiencing is not isolated to just westernized nations: it is a worldwide occurrence.

Recent BIS data indicates that the return of inflation, although most pronounced in the U.S., is global.[1] While inflation rates are now over 5% in 58% of advanced economies, they are over 7% in 55% of emerging economies. This isn’t all due to energy — inflation, when measured to exclude energy, has also accelerated widely due to a supply/demand mismatch. The data suggests that U.S.-specific factors, such as President Biden’s stimulus last year, may only explain one or two percentage points of the rise in inflation.

BIS: High Inflation is a Worldwide Phenomenon

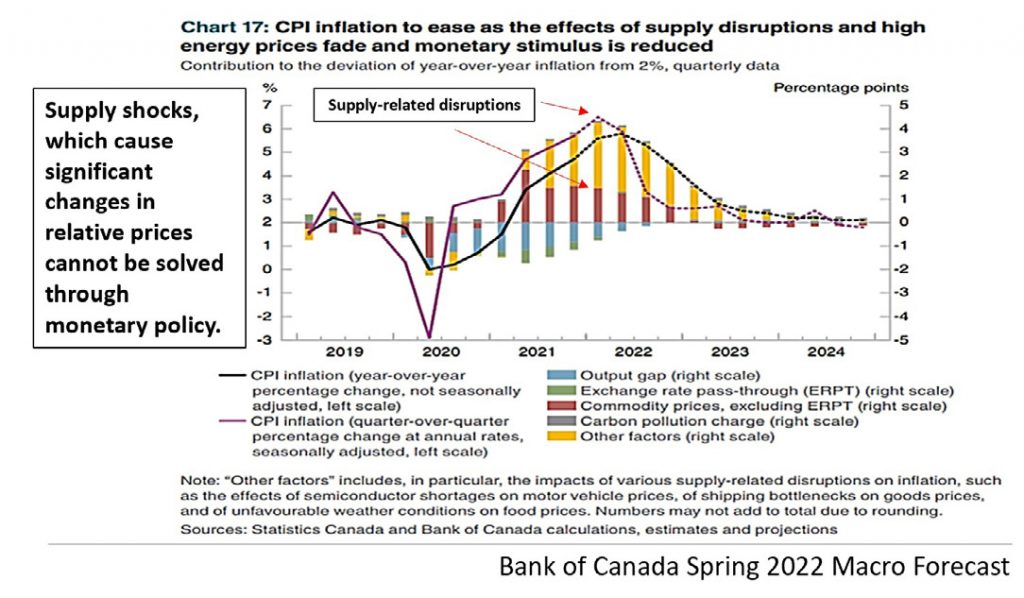

Similarly, thought leaders at the Bank of Canada concur, [2] as evidenced by their recent analysis. The vast majority of inflation can be attributed to “other factors,” specifically supply chain disruptions.

Bank of Canada: Inflation & Supply-Related Disruption

Ironically, the day before Chairman Powell would communicate his newly hawkish stance, San Francisco Federal Reserve President Mary Daly suggested that continued patience was needed. In a presentation on her spring outlook, she ended the speech with the following story, none of which was reported by the media:

“Let me leave you with a story that illustrates my approach to policymaking and how I will navigate the challenges ahead. As a teenager, I worked at a donut shop. Part of my job was to drive a delivery truck…I sometimes went a little too fast. I wound up losing my license for three weeks, which felt like a lifetime. That youthful mistake taught me a valuable lesson. Getting there is important…but, so is the journey. In my attempt to get there quickly, I actually didn’t get there at all. A smooth and methodical approach to policy will alert us to hazards along the way, prepare us for unexpected bumps in the road and ultimately keep us moving forward…” [3]

Textbook Lessons From ECON 201

Why does this matter? The word “inflation” is often inaccurately used to refer to any increase in prices. Yet, true inflation — from a purely economic perspective — should not be confused with price increases due to changing supply and demand conditions, referred to as “relative-price changes.” In these circumstances, monetary policies cannot alleviate these price changes. The parabolic increases witnessed in the price of used cars serve as a good example — chip shortages due to supply imbalances were the primary culprit, not any underlying economic factors that would be remedied by monetary policy actions.

We see this today as a result of the dual shocks of Covid-19 and the Ukraine conflict. These two events have led to extreme changes in relative prices — and not changes in the general price

level. To be clear, central banks can do nothing about movements in these relative prices.4 Raising interest rates won’t reduce the bottleneck at ports, accelerate the flow of oil or natural gas or harvest more wheat. What is quite worrisome is that many so-called economic experts suggest that interest rate hikes are the magic antidote to these problems.

Raising rates can help to alleviate certain pressures in cyclical areas of the economy, which are already slowing due to the extreme fiscal drag we are experiencing. However, the relative price changes we see today need to be solved by the economy going through a period of structural adjustment. Markets, if given time, will adjust and excess rents will eventually be reduced — a fact that too many seem willing to ignore. Markets do adjust when left to their own devices; the current attempt to micro-manage the business cycle by central bankers needs to be abandoned.

On the Verge of a Policy Mistake?

To this point, Powell has been patient, flexible and has relied on the data — and further patience is needed. Like a credible coach of a well-practiced team can afford to lead with minimal gestures, so too should a credible central bank let inflation evolve within a wider range of its target. It is my belief that increasing the policy target to 3% and allowing high prices caused by extreme relative price changes to adjust on their own would reallocate capital — let’s allow the generational adjustment process to continue.

Should the Fed tighten over 350 bps, it will be too aggressive and risks sending the economy into a recession, slowing the natural and needed adjustment process.

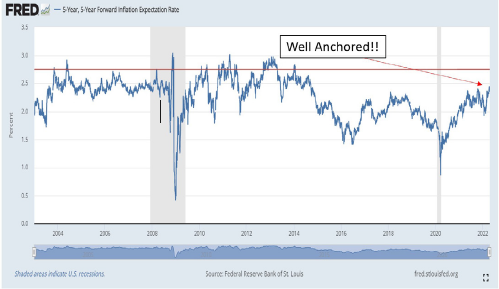

Long-Term Inflation Expectations: Well Anchored

However, it would not be a surprise if today’s hawkish stance spurs a new debate around raising the inflation target to 3%. Price stability at 3%, alongside patience, may allow prices to rapidly adjust to the influx of capital while not sending economies into a severe recession — a solution that central bankers should examine.

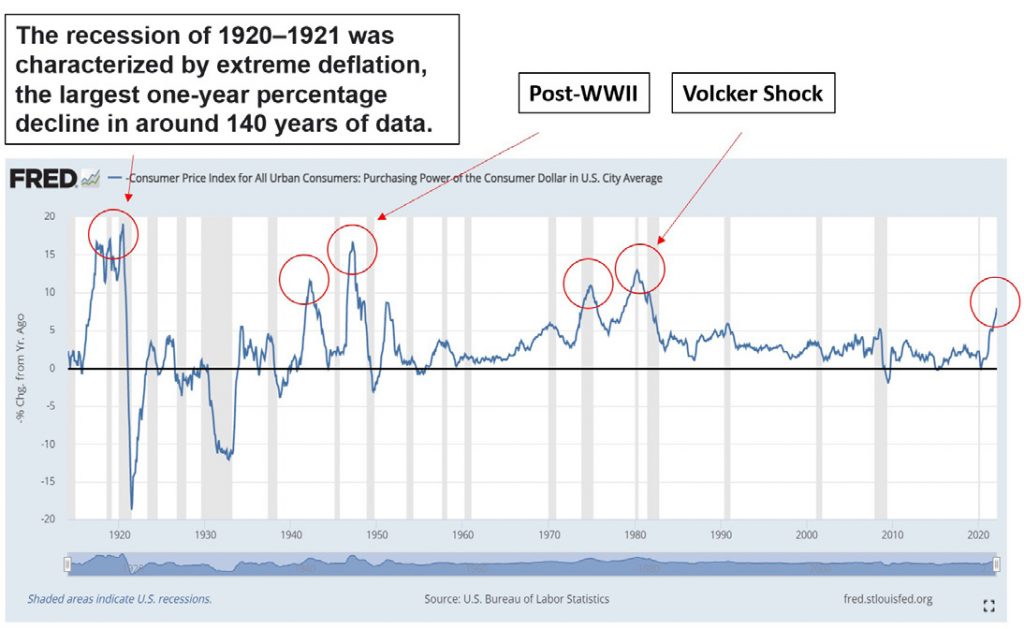

History’s Lessons: Beware the Consequences

The five-year five-year forward series acts as a solid guide. My base case assumes that as the economy slows and prices decline, the Fed will not bow to political pressure and aggressively tighten as it did in 1919 or the late 1970s. History reminds us of the consequences. Since the Fed’s inception in 1913, we have experienced five episodes of extreme inflation. Following WWII, during a period of extreme structural adjustment and when debt-to-GDP was close to 130%, the Fed could not raise rates and instead controlled inflationary expectations predominantly by using a communication strategy — akin to what should be happening today.

This contrasts with the actions taken in other periods. In the episodes after WWI/Spanish Flu and the 1970s, policymakers implemented extreme measures that led to a severe deceleration in economic activity and unleashed significant deflationary forces. Milton Friedman characterized this as the Federal Reserve policy mistake that caused the Depression of 1920-21!5 What was overlooked in these cases was that the prevailing price increases were largely relative price changes

caused by exogenous shocks, just as we see today.

Episodes of High CPI: Deflation Followed

Canadians should also not forget the actions taken in the late 1980s by John Crow, former Bank of Canada Governor. His conquest to defeat inflation sent the Canadian economy into a deep recession, crashing the housing market into a correction that lasted over a decade and creating significant unemployment.

To wit, today’s policymakers face a difficult decision: abandon the patience approach implemented after WWII and let the economy adjust naturally, or apply extreme monetary tightening. The latter will rapidly slow the economy by contracting cyclical areas, yet prolong the adjustment process and send the economy into a recession. We are already seeing the U.S. economy contracting, with Q1 2022 GDP at -1.4%. Cyclical contraction does not alleviate relative price changes caused by exogenous shocks, except in the case of an extreme cyclical contraction of the economy as seen in what many call the “forgotten depression of 1921.” In the cases where extreme measures were used, a hard landing was the inevitable result.

Fed Independence Should be Sacrosanct

The Fed’s change in direction is somewhat bewildering to those who rely on data to make decisions. Are central banks becoming political puppets? While it is impossible to fully understand the underlying drivers for the new hawkish stance, some observations can be made. Governments have always used economic policy to increase their chances of staying in power. We find ourselves in a mid-term election year, a time when political impact is most important as many members of Congress are up for election. There has been relentless media coverage of the damage caused by persistent inflation — the beast that has wreaked havoc on the average citizen, increasing the cost of living and threatening the quality of life. The Biden administration is being blamed for its lack of action, not a highly unexpected reaction in this world of instant gratification. At the same time, it is curious that the reappointment process for many members of the U.S. Federal Reserve, including Chair Powell himself, has had significant delays and voting has largely been along party lines — another sign of possible politicization?

However, it is my belief that the independence of the Federal Reserve remains of utmost importance. While there will always be an intrinsic link with the government, intrusions into the fiscal space and political arena risk harming the Fed’s independence and credibility. Notably, the concerns about income inequality and climate change that were broached by Powell and other central bankers prior to the pandemic — while of importance and needing to be addressed and rectified — should not be explicit policy goals of the central banks. The Fed’s independence is sacrosanct.

Investors Take Note

Given the Federal Reserve pivot, investors should take note. While we have experienced a rise in the general price level, I contend that it is much less than what has been priced into the markets, even with this new hawkish stance. With weaker economic data and declining prices, the credit market may be too aggressive in pricing in the tightening. The changing market dynamics may have caused this false signal in the capital markets. More specifically, the lack of liquidity and the use of ETF, options, leverage and structured products suggest that the move in the two-year yield may not be as informative as it was in the past. As the year progresses, the likelihood is that the sustained, excessive price increases experienced from the dual shocks will not be repeated.

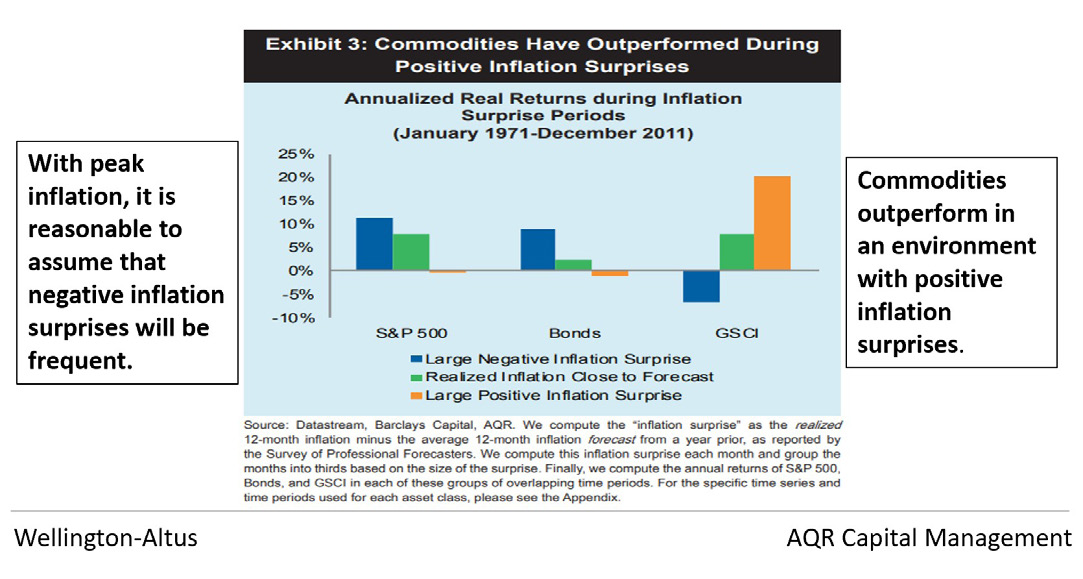

Should the central bank not make a policy mistake, we may have reached interest rate and inflation near highs. As inflation surprises temper, we would expect commodities prices to decline. Research by AQR reveals that once inflationary expectations cease to surprise to the upside, the extreme outperformance of commodities vanishes.6 The time to position for the inflation trade was in late 2020 or early 2021, as suggested in past Market Insights.

Commodity Performance & Inflation Surprises

As the year progresses and the economy continues to adjust, economic performance will slow and disinflation will become more evident — likely a surprise for many. Investors should not be surprised if the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury closes around 2% by year end.

As always, investors need to be flexible and have a high degree of humility. With the consensus trade being long inflation and short bonds and technology, a reversion to the mean trade cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, with consensus piled into defensive sectors, which are now very expensive, and with pessimism at extreme generational highs, any signal that central bankers are moderating their ultra-hawkish tone could result in a violent rebalancing.

For now, the lows in the stock market should not come as a surprise. We entered 2022, a mid-term election year, expecting a messy first half and suggested that investors be positioned defensively, with equity returns being back-end loaded. With earnings growth in the low double-digits and with lots of bad news already priced in, a rally into the end of the second quarter would not surprise. That said, equity returns are still expected to be back-end loaded in 2022.

What will cause a change in this position? Conclusive evidence that the Fed and the Bank of Canada are not data dependent.

It is true: you are what your record says you are. For now, anchoring to the post-WWII era provides the best guide for central bankers. In that period, the record for the Fed navigating troubled waters was pretty good.

— James E. Thorne, Ph.D.

References

[1] The Return of Inflation, Agustin Carstens, April 5, 2022.

[2] Monetary Policy Report, Bank of Canada, April 2022.

[3] Steering Towards Sustainable Growth, April 20, 2022.

[4] Rising Relative Prices or Inflation: Why Knowing the Difference Matters. Owen F. Humpage, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, June 1, 2008.

[5] The Monetary History of the United States, Freidman and Schwartz, 1963.

[6] Building a Better Commodities Portfolio, AQR Capital Management, September 2012.