Download this article as a PDF.

“Always make the audience suffer as much as possible.” — Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock once suggested that drama is life with the dull parts cut out. Given the state of the financial markets, this has never been more relevant than it is today. The first half of 2022 has been characterized by significant drama, leading to considerable suffering for those who reacted hastily to the ensuing volatility.

We entered the year with a dichotomy of narratives for economies and financial markets — rebirth and tragedy. While consensus suggested tragedy, there were less conspicuous reasons for rebirth. Indeed, a focus on the current state of the credit markets suggests that the narrative of rebirth is now playing out, but not before considerable drama has taken place. The credit market tightened at a pace not seen historically and now has pivoted, implying that a peak in rates has occurred for the cycle: growth is slowing and inflation is no longer the prime concern.

Is the Fed behind the curve? As I have suggested in the past: No. Instead, the Fed has wisely influenced the credit markets through its communication strategy and should now follow its lead. As the capital markets realize the error of their ways — they’ve tightened too much — interest rates will continue to decline and multiples will expand. We are seeing its beginnings today. Investors take note: the controversial long-duration asset trade is expected to take hold, which will shift the narrative of many market pundits from tragedy to rebirth.

What’s Happening in the Credit Markets?

To start the year, it was suggested that central bankers could take two paths. The first relied on central bankers anchoring off the cognitive bias that interest rates were the only policy tool available. If this path was chosen, Maslow’s Law of the Hammer would dominate, likely leading to a recession or financial crisis. The other path was what we have referred to as clinical inertia: do nothing and let the economy and markets adjust to the shocks. Policymakers could use a communication strategy to anchor long-term inflationary expectations, in what Lord King referred to as the “Maradona effect.”

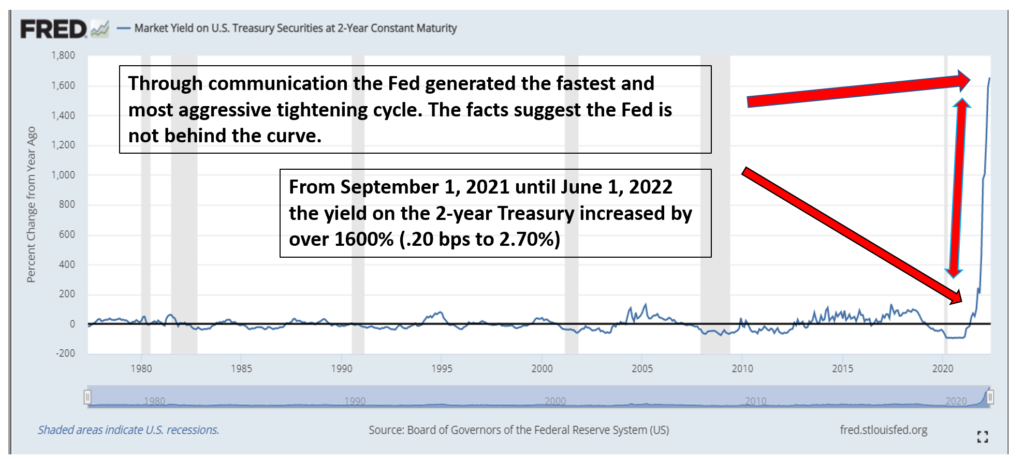

The Fed has been successful in invoking the latter: manipulating the credit markets through communication. Their uber-hawkish communication strategy to end the year created the most intense tightening cycle in modern history. Those who follow the credit markets are acutely aware that interest rates have risen significantly over recent quarters. In fact, since September of last year, the yield on the two-year Treasury climbed by over 1,600%! This occurred while the Fed only raised its key interest rate from 0.25% to 1.0%, or only 300% over this time.

Historic Tightening Cycle: All Driven By Fed Communication

The credit markets have now started to pivot and interest rates are starting to decline. This was expected as the markets switched their focus from high inflation to slowing growth. The facts show that the yield curve peak is at its lowest since the 1980s, implying structural weakness in the economy and suggesting that growth is much lower than many uber-inflation hawks once believed. This also indicates that the terminal Fed funds rate is much lower than expected by those who proclaim inflation is permanent and suggests that we should rapidly raise rates to over 5%. To wit, the tightening cycle and the inversion of the yield curve have occurred without the Fed substantially raising the key interest rate.

The Fed Has Never Been Behind the Curve

Those who have denounced the Fed for not taking rate action sooner — the Fed is behind the curve — evoke a subtle point: the Fed has always followed the credit markets. The Fed uses moral suasion to influence the credit markets and, as evidenced by its current state, it has worked.

Developing a narrative based on the long-term evolution of the global economy can help investors view the past six months as an opportunity — and not the end of the world. When the Covid-19 crisis hit in March 2020, the Fed’s response was to invoke Section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act. This was an unprecedented action, which supports the belief that the Fed will also pivot from its hawkish stance much earlier than consensus is assuming. As the Covid-19 crisis unfolded, for only the third time in history it supported the deployment of direct lending tools to ensure that the economy was stabilized and companies would not go bankrupt, with the intent of enabling a quick recovery from this once-in-a-generation crisis. The Treasury would deposit close to $450 billion into the Exchange Stabilization Fund; the Federal Reserve would gross that total up by ten times and the Treasury would distribute these resources directly to support the economy. In essence, the Fed took a back seat to the Treasury in supporting the economy. This action sowed the seeds for the high inflation we are experiencing today, as well as the fiscal drag that is now contributing to slowing growth.

The Fed appears to understand that inflation is not a monetary policy phenomenon. Japan is one example of how quantitative easing (QE) can be deployed over decades and still not support increases in inflation. For economics scholars, the Fisher Effect suggests that for inflation to be a monetary phenomenon, the velocity of money must stay constant. Over recent times, we have seen that the money velocity has been decreasing. One such example can be found in the reverse repo market, which soared to all-time highs in 2021, suggesting that the reserves were not getting to Main Street.

Elsewhere, we see examples of central banks not aligned with this concept and the consequences are palpable. In England, the central bank has been raising rates with the intent of slowing consumption and bringing aggregate demand down, while the government is giving funds directly to citizens — the exact cause of this temporary inflation spike — to cushion the blow of inflation. It’s no wonder that inflation rates continue to rise; the consequence of a puzzling policy disconnect.

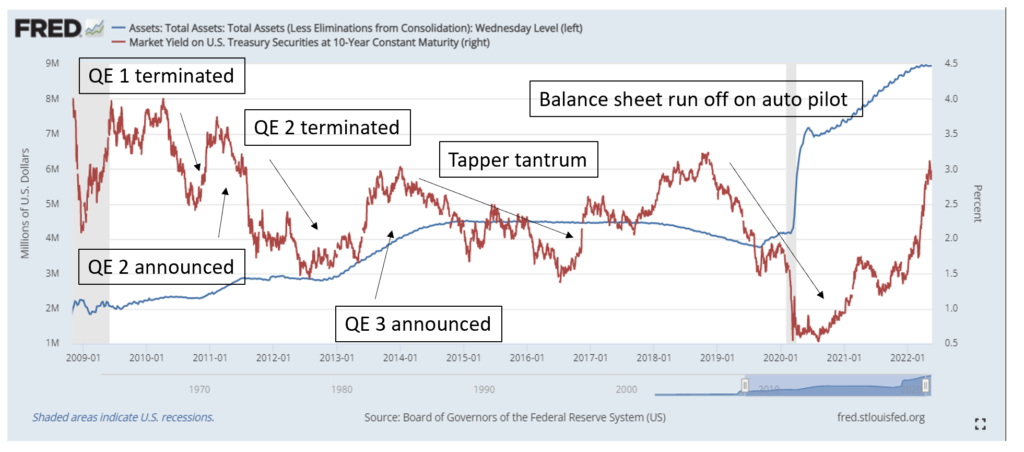

We must also acknowledge that, contrary to what consensus suggests, once quantitative tightening begins, interest rates in sovereign bonds will decline. Using the post-WWII era as our guide, the Fed has reduced the size of its balance sheet as a primary driver of controlling inflation expectations in the past — such as in the late 1940s, when the U.S. economy experienced three years of average inflation over 10%. Investors need to consider that once the contraction of the balance sheet begins, interest rates in the credit markets will decline. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond declined by almost 15% in May, just in anticipation of Quantitative Tightening (QT), which is set to start in June.

When the Fed Starts QT, Interest Rates Go Down

The Fed will eventually need to pivot from its current position. Otherwise, there is always the risk of tragedy. With the global economy having extreme levels of debt — the U.S. alone has 140% debt-to-GDP — any period of excessive tightening by the Federal Reserve could result in a corporate debt crisis. It is one thing for spreads in high-yield bonds to blow out, but if this extends to investment-grade bonds we could have a contagion on our hands. Furthermore, it’s been well observed that there are risks created by a period of extreme tightening by the Fed — the potential for an emerging market debt crisis or currency crisis, as we witnessed in Asia in 1997. Those who are egging the Fed on to further raise rates fail to see the risk of this approach ending in tragedy.

History’s Lessons: The Case for a Secular Bull Market

Contrary to consensus, history’s lessons suggest a story of rebirth. The twin shocks of Covid-19 and war have put additional headwinds on global economies, but economies were already under pressure prior to these shocks. The imbalance was planted in the Bretton Woods agreement and unleashed with the austerity Main Street had to endure after the global financial crisis. Yet, this has happened many times in modern history. L. Frank Baum’s book “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was a political allegory that focused on monetary policy, the rise of populism and the need for structural change in the U.S. economy in the mid-1800s, caused by the first industrial revolution and the shift from an agrarian economy to a manufacturing economy. The Wicked Witch represented the status quo, Dorothy the average American, the Scarecrow the farmers and the Tinman the mistreated factory worker. (Perhaps we can suggest that just as history once followed the yellow brick road, the Fed should continue to follow the path of the credit markets!)

Unbeknownst to many, the imaginary land of Oz has the same name as the abbreviation for the measure used to quantify gold and silver — the ounce. In this context, just as silver captivated the attention of the masses coming out of the Civil War, one can easily understand why blockchain, and its first incarnation of cryptocurrencies, has captured the interest of so many. How soon we have forgotten the infamous speech “Cross of Gold” delivered in 1896 by William Jennings Bryan — the Cowardly Lion — at the Democratic National Convention: “Having behind us the commercial interest and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

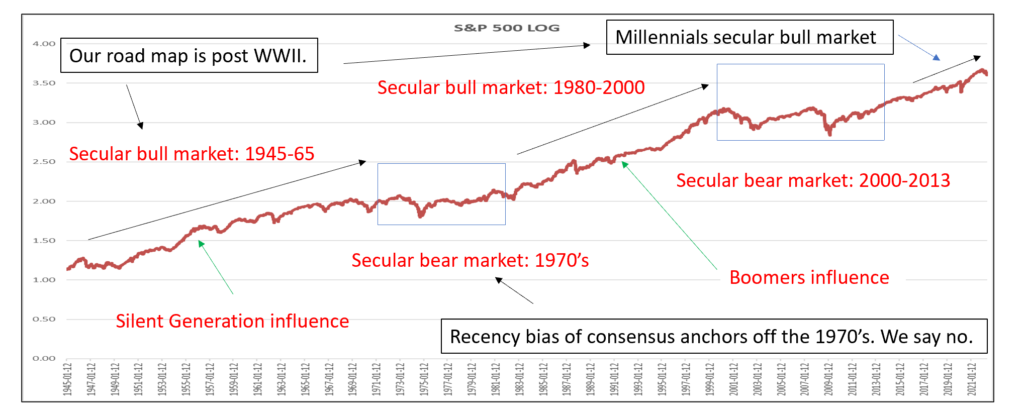

However, more profoundly, we are reminded that periods of intense structural change, where the status quo fights against the forces of progress, are very common in history and happen frequently. As with any shock to an economic system, the existing forces of evolution are amplified and accelerated. To be clear, the foundations of the theory of secular stagnation and the demographic study in the Fourth Turning, referred to in past Market Insights, are all variations of this long-term secular cycle. These periods of extreme structural change should be viewed as times of opportunity. As such, I remain bullish on risk assets for the long term, just as the post-WWII-narrative would suggest. We can expect a period of financial repression, where we can grow out of the current excessive levels of debt, followed by a period of strong economic growth, led by fiscal policy that is propelled by the green economy, a commodities supercycle, the reshoring of supply chains, millennials in prime family formation years and the rapid adoption of new technologies.

Secular Bull and Bear Markets From 1945

The risk, as also suggested by history, continues to be deflation. Technology, demographics, secular stagnation and extreme levels of debt are all strong deflationary forces waiting for us on the other side of this temporary inflation spike. This will upset those who continue to suggest that high rates of inflation are permanent and we have entered a new inflationary era — the facts simply don’t support this thesis. The Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have just accelerated and intensified the adjustment process. Consumer preferences for value have not changed: higher prices will create demand destruction and inventory build-up will eventually lead to price cutting; the tightness in the labour market is beginning to loosen; and investment will slow until visibility returns.

Where to for Investors?

The 2022 forecast continues to play out as was anticipated: in the back half of 2022, investors should expect the Fed to pivot, interest rates to decline, the USD to weaken and concerns about growth to replace inflation fears, resulting in capital flowing into long duration assets.

It is expected that the economy will continue to slow over the next few months. Based on the first quarter earnings calls of many companies, there is evidence of climbing inventory builds and plans to reduce workforce levels. As the economy slows and prices decline, the Fed will need to pivot. Investors should focus on the signals coming from the credit and equity markets and ignore the noise created by pundits. The credit markets have pivoted. The Fed and the equity markets will eventually follow.

We entered 2022 suggesting that the traditional mid-term election year cycle would be followed. In this cycle, the stock market has corrected, on average, between 18 and 20%6 in the first half of the year; but, once the bottom is reached and political uncertainty is reduced, the market rallies. As such, the fourth quarter of 2022 and the first two quarters of 2023 are forecast to be the strongest quarters of the four year market cycle. With the S&P 500 peaking at 4,800, a typical correction would bring it to 3,840. A growth scare was expected, and it is also anticipated that the Fed and the Bank of Canada will pivot before causing severe damage to the global economy. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that fiscal policy will become the dominant policy tool, as it was in the post-WWII era. It may be curious to note that the Bank of Japan has not followed its western counterparts in raising rates. For investors, this suggests that the early stages of a new era may be imminent where the Yen carry trade retakes centre stage in providing global liquidity, as was the case decades ago.

Investors need to be aware that the credit markets and the currency markets are starting to push back. To wit, interest rates on the long end have started to decline, as they have whenever the Fed tightens. In other words, the high conviction trade right now is to buy government bonds. My call is that investors should expect interest rates in the credit markets to decline throughout the year. Yes, the Fed lags the credit markets, it always has, but it has been successful in manipulating it through communication. I believe that the peak in rates for this cycle is now beyond us and interest rates should be expected to decline into year end. As predicted, the stock market has had its correction, and we have likely seen its bottom.

The anatomy of a correction suggests that we have just exited the second phase of a three-phase process. Phase one: strong USD. Phase two: interest rates on the long end start to decline. Phase three: long duration equity assets lead the market out of correction. We have experienced the first two and investors should take note that a rebirth may be upon us.

As I have said before, investors should remember that history reminds us to never let a crisis go to waste. While the plot of tragedy often draws more attention — a narrative that inevitably leads to catastrophe has always been more compelling — the words of playwright George Bernard Shaw are perhaps a fitting reminder for investors today: “If history repeats itself, and the unexpected always happens, how incapable must Man be of learning from experience.”

— James E. Thorne, Ph.D.

[1] Monetary Policy: Practice Ahead of Theory. Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, 2005.

[2] It peaked at 3.175%.

[3] Capital Flows Bonanza, NBER Working Paper 14321, Carman Reinhart, Vincent Reinhart, September 2008.

[4] The Historians Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum’s Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory. Edited by Ranjit S. Dighe.

[5] William Jennings Bryan, Democratic National Convention, Chicago, July 9, 1896.

[6] Stock Traders Almanac 2022, Jeffery A. Hirsch, 2022